|

|

Carmelites of Compiègne |

|

|

Carmelites of Compiègne |

To Quell the Terror: The Mystery of the Vocation of the

Sixteen Carmelites of Compiègne

Guillotined July 17, 1794.

by William Bush (ICS Publications Washington, D.C. 1999)

CHAPTER

7: MYSTERIES,

MARTYRS,

and RITES

of the NEW

ORDER

DAILY MASS in St. Antοine’s church was assured for the expelled nuns only until Abbé Courouble’s departure at the end of November 1792. After less than three months their comforting daily union with the sacramental presence of the immolated Beloved came to an end. Yet, as they continued to offer themselves for holocaust through their dally recitation of the act of consecration after their chaplain’s departure, the act itself became a powerful manifestation of his presence. In-deed, the only peace available to them came from being utterly reliant on him alone. Never had the verses of their holy mother-foundress seemed more timely:

Thine I am,

born for Thee,

What then wouldst Thou do with me?

Beginning in 1793 we know that Abbé de Lamarche, in the course of periodic visits to Compiègne to minister to the faithful, ministered also to the Carmelites. Still his periodic Masses could never replace the reassuring grace of a regular, daily Mass with its sacramental manifestation of the Beloved in their midst, day in and day out. But Abbé de Lamarche sustained and encouraged the community in their newfound vocation of absolute self-offering, and we have already seen how he so gently reconciled the young Sister Constance to death by the guillotine. Like a Christian in the early church, this exceptional priest knew how to venerate the presence of the Holy Spirit in those who were being called to witness with their blood.

EVEN though the fact was not announced by the revolutíonary government until October 5, 1793, we have seen that, according to the Republican calendar, “day One, of year One, of the One Indivisible French Republic” had dawned on the first equinox after the fall of the monarchy, September 22, 1792. Yet, in the chronicles of the Revolution, the significance of September 1792 went well beyond its being the month that served, albeit retrospectively, to mark the beginning of a new era in human history.

No month in that long stretch of months during which France was being purged of the old order proved more astounding. With the continued, and heretofore unthinkable, incarceration of the royal family, with the appalling blood bath of the massacres as that month began, and with the expulsion of the last religious from all surviving monasteries, September of 1792 proved a startling break with the past.

|

|

|

Procession and Enthronement of

an Actress |

|

|

September of 1792 also saw the end of the Revolution’s Legislative Assembly. Before disappearing, its members provided for the conversion of the former machine hall of the now-deserted Tuileries Palace into an assembly hall for the newly elected National Convention. Renovations would not be completed, however, until May of 1793.

In the meantime, workmen constructing the new assembly hall could sometimes watch revolutionary justice being administered on the Place du Carrousel by merely looking out the windows. About once a week Sanson, Paris’s executioner, could be seen there setting up the guillotine, assisted by his valets. Since the crime for which most of these prisoners were losing their heads was that of having defended the palace’s royal occupants against the “patriots” storming it on August 10, the government deemed a last sight of the ex-royal Tuileries Palace particularly salutary for the condemned. Punishment at the scene of the crime held a strong pedantic appeal for the moralists of the virtuous new order when dealing with political prisoners. Indeed, on August 17, 1792, just seven days after the August 10 upheaval, a distinct category for political criminals had been introduced into French justice and a special court created for dealing with all those “criminals” of August 10.

The new order found reassurance in the fact that, following the guillotine’s inauguration on April 25, all prisoners condemned to death, regardless of their social status, would benefit from its egalitarian dispatch. Still, even with the classless guillotine, executions for criminals of common law continued to take place at the age-old execution site of the Place de Grève. Only those falling into the new political category were brought to the ex-royal setting of the Place du Carrousel for their punishment.

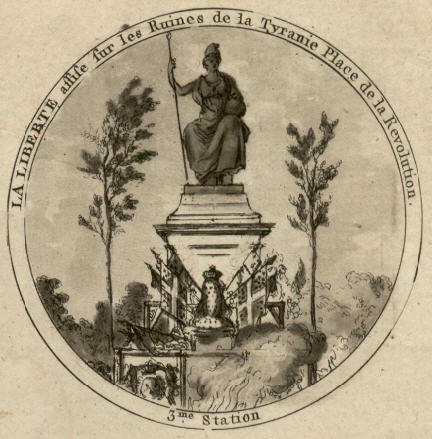

At the end of the eighteenth century the Place du Carrousel was almost completely enclosed by the Tuileries Palace, juxtaposed as it was to a wing of the Louvre. Because of its enclosed nature it would be eschewed for the king’s executiοn on January 21, 1793. Rumors of attempts to abduct and free the august prisoner were abroad. The place of the executiοn must allow for the free movement of troops and the open spaces of the Place of the Revolution (Place de la Concorde) were therefore favored. There both the massing of troops and the presence of thousands of witnesses to the regicide were possible. The new government also savored the prospect of beheading France’s “most Christian” king at that ex-Place Louis XV, constructed in honour of his immediate predecessor and grandfather. Its fine marble statue of Louis XV, toppled and smashed, had been replaced by a politically correct statue of “Freedom” in common plaster.

Following the January 21 regicide, however, the guillotine did return to the Place du Carrousel. There, about once a week, it continued to function until May 8. Members of the newly elected National Convention were scheduled to move into their renovated hall on May 10, however, and the more squeamish representatives, it was decided, must be spared. The risk of witnessing the administration of the new order’s justice just outside their new assembly hall windows thus prompted them to move the guillotine definitively on May 8 to the Place de la Revolution. There, as the new order gained momentum, it functioned ever more frequently, particularly after October 5, 1793, when the ten-day décadi replaced the seven-day week. By the end of the 13 months it remained there, it was dispatching an average of 14 political prisoners per day, nine days out of ten. Only on the eve of June 8, 1794, in preparation for the Festival of the Supreme Being, would it finally be moved elsewhere.

Meanwhile king and beggar alike were beheaded with no distinction, and with egalitarian efficiency, as the new order’s goal of supplanting Christianity with a less fanatical religion was ardently pursued. Outdated superstitious nonsense about Jesus Christ, that Jew whom Christians believed to be the virgin-born Son of God, and who rose from the dead, were things to be relegated to France’s pre-Enlightenment past. Indeed, what could prove more inimical to progress and the modernity of the new philosophical thought than Judeo-Christian superstitions rooted in seven-day weeks, sacrificial lambs, scapegoats, victims of holocaust, or a God who counts every bird that falls (Mt 10:29)?

7.3. Execution of the king; Le

Peletier de Saint-Fargeau, first “freedom

martyr”; the creation of the Pantheon; David and the enshrinement of

Voltaire and Le Peletier de Saint-Fargeau

AS if tο underline the rampant dechristianizatíon following the August 10 fall of the monarchy, no church bell would sound in all of Paris on December 25, 1792, even though the new calendar had not yet been proclaimed. Just twο weeks before that historic silent Christmas, on December 11, 1792, the king had been put on trial before the National Convention. The conjunction of this silent Christmas with the king’s trial was hardly amiss, given that the new order was aware that it had been on Christmas day, 496, that St. Rémi had baptized Clovis and anointed him as France’s first Christian king at Rheims.

Four weeks after that uncelebrated Christmas, on the morning of January 21, 1793, the king, attended by a nonjuring priest and condemned to death by a one vote majority—361 to 360—was guillotined. The close vote reminded the revolutionary government that a cult would undoubtedly spring up around the “martyr-king.” It was urgent, therefore, for propaganda purposes, that a countercult for a purely revolutionary martyr be created forthwith.

The needed subject conveniently fell available on January 20, the eve of the king’s execution. He was an aristocrat-turned-revolutionary named Le Peletier de Saint-Fargeau, representative to the National Assembly. Having voted for the king’s execution that day, he had the misfortune, that same evening, of encountering a saber-wielding member of, the former Royal Guard named Pâris. In crazed desperation over the death sentence, Pâris had gone out, sword in hand, determined to slay an acquaintance who, he learned, had voted for the king’s death. Happening first upon the unknown Le Peletier de Saint-Fargeau, who readily admitted that he too had voted for execution, Pâris immediately pierced his chest with a single thrust. The aristocrat turned-republican expired without delay.

Revolutionary propaganda moved quickly to exploit this “martyrdom for freedom,” occurring in such a timely fashion. Jacques-Louis David [athiest painter, ardent revolutionary, theatrical organizer of anti-Christian pageants, and survivor of the Terror, Napoleon, and the Restoration], whom we have encountered, was designated to organize the lying-ín-state and the pageant-procession to follow the state funeral on January 24. Hopefully the impact of a public pageant of “canonization” for this newly proclaimed first “freedom martyr” would prove a successful coup of propaganda, bewildering the confused masses and deflecting criticism from the regicide.

Voltaire’s Funeral

David’s rare talents for such public funeral rites had been brilliantly demonstrated for the first time just a year and a half before. On July 11, 1791, he had been responsible for the elaborate procession and ceremonies for the state funeral for Voltaire’s ashes, finally returned to Paris to receive government honors and be enshrined in the new Republican “Pantheon.”

|

|

|

The Pantheon - Intended originally as the Church of St. Genevieve |

It had been in the spring of 1791 that the revolutionary government commandeered the nearly completed domed ecclesiastical masterpiece of the architect Soufflot. Crowning the Montagne Sainte-Geneviève in Paris’s Latin Quarter where Paris’s sixth-century patroness, St. Geneviève, had lived, the handsome new domed structure was to replace the ancient and now-demolished church housing her relics.

Louis XV had underlined its importance by his royal presence at the blessing of the new church’s first stone In 1791, however, the new order secularized Soufflot’s monumental masterpiece to create a national mausoleum. Thus, as the church of St. Geneviève became a strictly male preserve, proudly limited to the earthly remains of a “grateful fatherland’s great men,” the ancient Christian cult to Paris’s spiritual mother was disdainfully cast aside. The enlightened men of the new order regarded such cults as superstitious nonsense, totally without relevance for the modern world.

The first body solemnly enshrined in the new national mausoleum was that of Mirabeau, whose sudden death in April of 1791—rumors said by poison—deprived the early Revolution of one of its illustrious leaders. Immediately afterward a clamor arose. In reparation for past neglect, should Voltaire, a great light of the new order and a father of the Enlightenment, not now have his ashes brought back to Paris for burial also in the new Pantheon?

|

|

|

Funeral Procession of Voltaire |

David’s all-day pageant-procession for Voltaire’s ashes on July 11 featured, in the middle of a very long parade, classically costumed characters from the author’s plays walking on either side of the sarcophagus-bearing float. Atop the sarcophagus reclined a life-sized wax figure of Voltaire, draped in a sheet, bare chest exposed, being proffered a crown by a waxen muse. It poured with rain the whole day and, hour after hour, as the funeral float progressed slowly across Paris, the rain gradually washed away the colors applied to the reclining wax figure. Upon finally arriving at the Pantheon that evening it was a cadaverous white.

Le Peletier de Saint Fargeau’s Funeral

Voltaire’s reclining posture was again favored by David for displaying the crowned cadaver of Le Peletier de Saint Fargeau on January 24 in 1793. It too was extended on a couch in the open air, but at the Place Vendôme, high up on the central pedestal where the pillar bearing a statue of Louis XIV had previously risen. The cadaver’s bared chest allowed the people to contemplate his fateful “martyr’s wound.”

|

|

|

Le Peletier de Saint-Fargeau |

|

|

For the state funeral and procession to the Pantheon members of the National Assembly were massed around the pedestal. Republican hymns were sung prior to escorting this first “freedom martyr” to the Latin Quarter. There Le Peletier de Saint Fargeau joined Mirabeau and Voltaire as one of the “grateful fatherland’s great men.”

Neither the enshrined Le Peletier de Saint-Fargeau nor most others entombed with republican pomp in the Pantheon was to prove immune, however, to those many and varying strains of political correctness chronically plaguing the new order’s government. Only the literary giant, Voltaire, was left to rest in peace. As for the others, manipulated polítícal enthusiasms kept dictating that the grateful fatherland’s great man ceremoniously buried there one day, subsequently be surreptitiously removed with as little afterthought as that of a courtesan carelessly casting off last season’s fashions.

7.4.

Marat, second “freedom martyr”; his

campaign against the Girondins; Charlotte Corday;

Marat’s apotheosis on the Feast of Our Lady of Mount Carmel.

ON July 13, 1793, a year to the day before the Carmelites of Compiègne arrived as bound prisoners at the Conciergerie, Marat was fatally stabbed in his bath by Charlotte Corday. The violent death of the Swiss-born, Edinburgh-educated doctor and former physician to the troops of the Count of Artois, proved as timely for the government as had the demise of Le Peletier de Saint-Fargeau. Although immediately seen by the new order’s government as the most perfect candidate possible for the role of second “freedom martyr,” David faced grave problems in the ceremonies accompanying his apotheosis.

Far more widely known than Le Peletier de Saint-Fargeau, Marat was recognized throughout revolutionary France for his vítrίοlίe Parisian newspaper, L ami du peuple. Fancying himself an important theoretical scientist and humanitarian, as well as “the people’s friend,” he illustrated this latter virtue by repeatedly calling for thousands of heads to fall in order to guarantee the success of the Revolution. His vociferousness was particularly virulent in regard to the Girondins.

Marat’s mid July demise was thus a double windfall for the government. Caught as it was in its spiraling campaign to purge itself of the powerful Girondin party, the canonization of “the people’s friend” as the second freedom martyr would win favor from the people and justify the government’s propaganda against the Girondins. Since June the government, not daring to carry out an instantaneous purge of such an influential party, had been obliged to content itself with placing the Girondins under house arrest.

Composed for the large part of representatives from the provinces, and notably from Bordeaux and the region around the Gironde River, the “Girondins,” in opposition to the Jacobins or prevailing “Mountain” faction, steadfastly opposed the Revolution’s being dominated by Paris. The Jacobins, however, working with the municipal government of Paris through the Committee of Public Salvation, were determined to impose Paris’s primacy. Though the June house arrests of the Girondins had temporarily silenced the opposition, the enraged Marat kept calling vehemently for their heads. Sympathetic to the maligned Girondins, Charlotte Corday was determined to silence Marat.

Twenty-five years of age and of a good Caen family, Charlotte Corday; was a great great niece of the classical dramatist, Pierre Corneille. She had made the long trip to Paris from Normandy all alone, intent on her self-imposed mission. Acting with the sublime determination and noble self-composure of a heroine from one of her great-uncle’s tragedies, she gained admittance to Marat’s apartment, then stabbed him in his hip-bath. As was his wont, Marat had been writing one of his inflammatory articles while soaking in his tub, seeking relief from the chronic itching of his diseased skin. “The people’s friend” thus died, pen in hand.

Charlotte Corday went to the guillotine four days later, on July 17, 1793, a year to the day before the Carmelites’ martyrdom. Combining youth, beauty, and daring with a rare capacity for coolly dispatching a popular, highly controversial journalist, she must have seemed symbolic of the Girondins themselves. Though personally admirable for her daring, she was guilty of crimes requiring her extermination for the good of the Republic.

Marat’s Funeral

The ceremonies for Marat’s lying in state as the Revolution’s second “freedom martyr” were set for the eve of Charlotte Corday’s execution, July 16, feast of Our Lady of Mount Carmel. With this second pierced cadaver David hoped to repeat his success at the Place de Vendôme, even though it was deemed more appropriate to stage Marat’s lying-ín-state at the Cordelier Club. Located in the former Cordelier Church, the Cordelier Club was the Jacobin Club’s most serious rival. It had also claimed Marat as its leading light.

But there were complications. Displaying a body with a gaping wound in the chill of mid January is not the same thing as displaying it in the heat of mid July. And the state of Marat’s body discouraged it. His skin disease, combined with the July heat, had caused decomposition to set in almost immediately. David was thus obliged to renounce his plan for displaying “the people’s friend” sitting up in his bath, his entire torso uncovered, in the position in which he was stabbed. Also reluctantly sacrificed were the propaganda advantages of a three-day lying in state.

Precautions had to be taken in displaying Marat’s body. For this purpose a very high stage was constructed above the former church’s altar so as to assure a prudent distance between the body and the public. Stretched out on a couch with chest uncovered, the martyr, with his gaping knife wound, would still be visible to all eyes.

|

|

|

|

|

Marat's Funeral |

To offset the inevitable smell, incense was burned continually in huge braziers, one set at each of the high stage’s four corners. Far less mystical but equally effective were the twο steaming cauldrons of vinegar, kept boiling on the high platform by twο male attendants who, stationed at the head of the dead Marat, were continually sprinkling “the people’s friend” by means of sponges soaked in antiputrefactive liquid.

When the doors were opened at noon to an eager public, would-be mourners avidly pushed their way in to gape at the extraordinary spectacle. High above them, at the center of the stage, they beheld Marat’s body. It was of greenish tinge and swathed in wet sheets, save for the exposed upper torso with its martyr’s wound. Even in death, they noted, “the people’s friend” still gripped his “immortal” pen.

In spite of the stench, the masses poured in. They stared, full of wonder, not only at the body high above them up on the incense-clouded stage, but also at the display below: the shoe-shaped hip-bath, the murder weapon, and the journalist’s ink stand, but especially Marat’s heart. Encased in an urn suspended from a vault in the Cordelier church ceiling, it was inevitably associated by the people with the popular cult to the Sacred Heart of Jesus. Wide-eyed and mouths gaping, they could be seen whispering reverently to their neighbor as they indicated the “Sacred Heart of Marat.”

The necessarily quick interment of Marat that same evening in a sealed lead coffin in the Cordelier church came only after a solemn but lugubrious torchlight procession of the body through the streets of Paris. Veiled women mourners accompanied “the people’s friend,” bearing the hip-bath, the murder weapon, and the ink stand.

This precipitous evening burial, however, proved but the first of a series for Marat. A less hasty one took place in the Luxembourg gardens at the beginning of August. Enshrinement in the Pantheon came more than a year later and was of short duration. Political correctness allowed Marat only four months there. He replaced the unceremoniously removed Mirabeau in November of 1794 but was himself similarly cast out in February of 1795.

At the time of his death, however, “the people’s friend” had certainly not lacked adulatory rhetoric. Wounded by the initial refusal of the Pantheon, one devotee compared Marat to Plato, Aristotle, and Socrates. He admitted that he had not known them, but his admiration for Marat whom he had known was just as great and posterity would give him his due.

|

|

|

Marat's Image Incensed with

Smoke |

At the funeral oration in the Luxembourg gardens in early August, the inspired orator went further still. Forgetting about the ancient Greeks, he took up a comparison with the God-Man of the Christians.

Sacred Heart of Jesus! Sacred Heart of Marat!

You have equal rights to our homage!

Marat and Jesus, divine men

whom heaven gave to earth to direct the people

in the way of justice and truth!

Comparing the Jacobins to the Apostles, the shopkeepers to the publicans, and the aristocrats to the Pharisees, he even drew an exaggerated parallel between the Virgin Mary and Marat’s concubine. Just as the former had saved the child Jesus from Herod’s anger, he observed, so the latter had saved “the people’s friend” from the anger of his enemy, Lafayette, former mayor of Paris and legendary hero of the American Revolution. Decisively confirming the superiority of Marat’s cult, the speaker concluded: “If Jesus were a prophet, then Marat was a god!”

LESS than a month after Marat’s July 16 apotheosis, a far grander ceremony was entrusted to David’s talents. This was the “Festival of Republican Unity,” celebrated on August 10, 1793, the first anniversary of the fall of the Christian monarchy. Since the final fate of the detained Girondins was still in abeyance, this August event aimed specifically at shoring up republican unity against the Girondin threat. It was also notable for introducing a rite of communion into republican ceremonies.

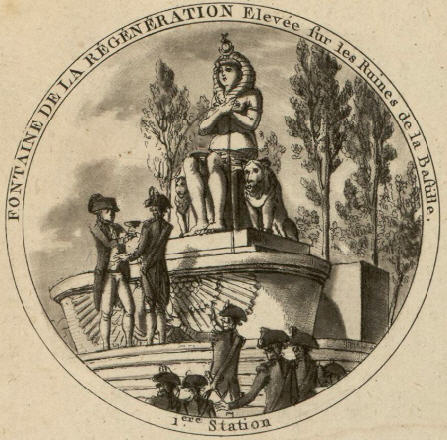

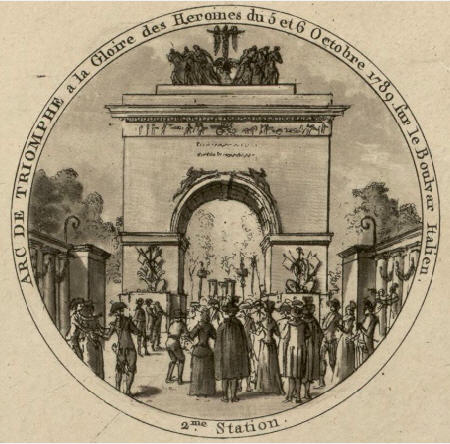

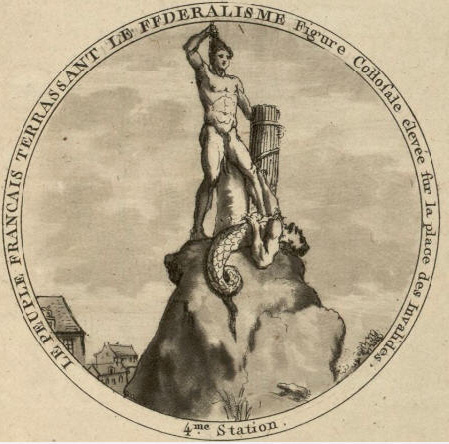

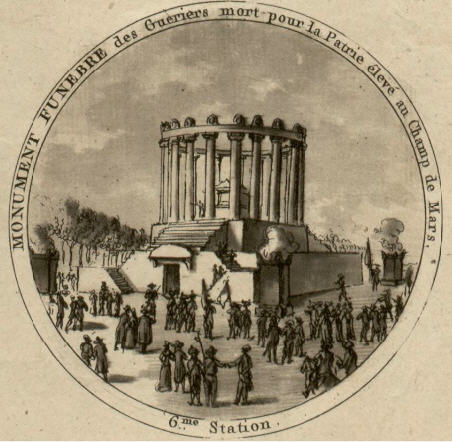

Processional Stations at the Festival of Republican Unity

|

|

|

|

|

The celebration was to take place at the Place de la Bastille, confirming the site’s increasing prestige, a prestige that had been carefully nurtured by a certain Citizen Palloy, the stone mason who had acquired the contract for demolishing the old fortress and became a successful Parisian businessman. Aware of holding the monopoly on any profits to be made from the old prison fortress, Citizen Palloy was not at all disinclined to tend the cult growing up around ft. Certainly the morbid curiosity of foreigners in search of Parisian thrills was obligingly titillated with horror stories of the old structure. Its fame abroad was thus assured, and the pro-republican idea that “the people’s Revolution” finally throwing open its dark doors was long overdue, became a common-place.

Citizen Palloy even built up a small industry selling the old fortress’s stones, whether as plain building stones, or carved into small likenesses of the old Bastille, or busts of famous men such as Voltaire, Franklin, or Washington. Even jewelry was fashioned from them. As revolutionary relics replaced Christian ones, Bastille stones came to be much in demand. No commune in France wished to be without its politically correct relic of the Bastille whenever it staged a patriotic event. Compiègne, rechristened “Marat sur-Oise” in the wake of Marat’s assassination, proudly carried its stone from the Bastille with due pomp and solemnity in all its municipal processions.

Citizen Palloy’s Bastille cult, destined to such lasting glory, proved quite successful in glossing over certain disquieting facts. Not only were there but seven persons being held in the old prison-fortress on July 14, 1789, but some of these prisoners actually risked their lives trying to save their kindly prison governor from the blood-thirsty “liberators” who gave all appearances of being no less intent upon beheading the Governor than upon liberating the prisoners. Totally disregarded was the prisoners’ informed evaluation of their own situation. The governor’s head was triumphantly paraded around as a sign of the “people’s victory” over “`tyranny.”

That it was at the site of the former Bastille that the delegates from each of France’s 83 départements gathered on August 10, 1793, for the Festival of Republican Unity was therefore hardly surprising. To underline Paris as the center for revolutionary unity, and to strengthen the Jacobin cause against the absent Girondins, David, as pageant-master, had the 83 departmental delegates each take a public oath swearing unity. He thereby offered the people, his program tells us, “the sublime spectacle of a nation of brothers embracing one another under the vault of heaven and swearing in unison to live and die republicans.” Each delegate surrendered to the President of the Convention the small tree branch he had carried in procession. At the end the President joined all of them together by means of a tricolored ribbon to form the “fasces” of the Republic.

Rather than feeding on the sacramental body and blood of the old Christian order, however, these representatives of a free people were to partake of the “pure and salutary liquor of regeneration” as the confirmation of their oath-taking. This “salutary liquor” shot forth in twο strong streams, one from each of the “fecund breasts” of Nature, embodied by a gigantic statue of a seated female nude, of heavy, graceless proportions, raised on the site for this occasion. Flanked by Egyptian lions and high urns burning incense, Nature dominated the large elongated water-filled basin below her into which gushed her twο jets of “pure and salutary liquor.”

|

|

|

|

Drinking from |

the Fecund Breasts of "Nature" |

Splendid in tricolor sash and tricolored plumes crowning his David-designed hat, each of the 83 delegates proceeded to this act of republican communion. Catching some of the streaming regenerative “liquor” from one of Nature’s jets in a chalice, he drank of it, then passed the common cup on to the next delegate.

David’s talent for propaganda ceremonies took on a more personal tone, however, on October 16, the day of Marie Antoinette’s execution. While the royal basilica at St. Denis was being sacked, we find him not only making his cruel sketch of the humiliated queen on her way to the guillotine, but also staging a ceremony honoring Marat and Le Peletier de Saint-Fargeau at the Louvre, where he resided. His portrait of each of the Republic’s twο “freedom martyrs” was solemnly displayed at the national museum that day in a quasireligious setting. Like miraculous icons set out for veneration and attendant graces, each canvas rested on its own sarcophagus, in its own improvised chapel, set off by tricolor bunting. A choir from David’s own revolutionary section in Paris came that day to sing funeral hymns before the twο images. Before departing, they all swore an oath to die for the nation.

Nor was the government’s deification of Marat and Le Peletfer de Saint-Fargeau as “freedom martyrs” limited to the efforts of David alone. We find them referred to in a play of Radet’s entitled Le noble routier.

Where Freedom’s friend is dwelling,

Where patriotism’s sincere,

We find Freedom’s twο martyrs,

Both gods that one reveres.

Busts of the twο “martyrs” graced the Revolutionary Tribunal’s deliberations.

AFΤER five months of Jacobin vilification, 22 Girondin leaders were finally executed on October 31, 1793. Those who had managed to slip away from Paris were later captured and executed; others took their own lives. Sympathizers and associates such as Madame Roland were also ruthlessly eliminated.

It was in the wake of that October 31 execution that Madame Roland’s celebrated words, “O Freedom! How many crimes are committed in thy name!” were uttered on the scaffold on November 8. Clad in white with hands bound, the beautiful young Girondin hostess raised her eyes to address Freedom’s plaster statue presiding over the guillotine in that fateful moment, before being strapped to the vertical balance plank.

The Girondin purge was only the first of several, how ever. Each one bound France more tightly in the embrace of a faceless terror. As astounding as each purge proved during the terrible, bloody spring of 1794, the fall of Danton and his associates provoked the most profound shock of all. They were executed on April 5, barely three months before the Carmelites of Compiègne.

The destruction of the 34-year-old Danton was indispensable, however, if his rival for political power, the “incorruptible” Robespierre, were to attain undisputed reign. At 35, Robespierre was just a year older than Danton. A lawyer from Arras and a priggish moralist with great personal ambition, he considered the battle against atheism a goal worthy of his fiery sense of personal mission. Robespierre was also particularly eager to fill the social vacuum created by dechristíanization.

The attempted cult to “Reason,” highlighted by the much publicized ceremony staged in November of 1792 in Notre Dame in Paris, had not really succeeded. Robespierre therefore opted for a cult to the Supreme Being that disciples of the Enlightenment would find compatible with their reading of the philosophers. Certainly it must be a more intellectually sophisticated religion than Judeo-Christian superstitions concerning the existence of a personal, self-revealing God who intervenes in history and is interested in our destiny to the point of numbering the hairs of our heads (Mt 10:30). Such ideas were esteemed childish fanaticism for any French citizen living in the enlightened age of the philosophers.

Robespierre’s Supreme Being, on the other hand, was a vaguely benevolent, largely indifferent creator deity. A free people could, with all of “Nature,” address hymns of praise to him with no fear of his irrupting into their private or public affairs. In the moralistic sentimentality of the eighteenth century’s euphoria as it deified “Nature,” the implacable cruelty of the natural order was forgotten. Indeed, as that century continued to seek rational concepts to replace the “primitive” God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, the unmitigated goodness of “Nature” and of “a free people” seemed to attain ethereal heights of beatitude in a sort of rosy, sublime ascension.

Scarcely a month after Danton’s April 5 execution, the 35-year-old Robespίerre persuaded the National Assembly on May 7, 1794, to pass a bill decreeing that all citizens of “the One Indivisible French Republic” believed in this nebulous Supreme Being. This astounding bill also included a second statement, equally fictional, proclaiming that all French citizens also believed in the immortality of the soul.

Sorely vexed by this May 7 bill, atheists in the Assembly were even more vexed when Robespierre, implacably pursuing his course, had a nationwide holiday voted to celebrate this fusion of religion and political correctness. The Festival

of the Supreme Being was set for 20 Prairial, Year II June 8, 1794, on the Gregorian calendar. For Christians it was the feast of Pentecost, birthday of the church of Jesus Christ and a Christian feast ranked only after Easter and Christmas.

TΟ ensure that the Pentecostal celebration in 1794 be the most elaborate display of republican propaganda yet staged in Paris, the National Assembly voted a budget of 1.2 million francs for David’s Committee of Public Education. A procession was to be featured in which, according to David’s program, the whole of Paris would take part.

Roused at an early hour by martial music, the city’s citizens, the program specified, were to “embrace one another with joy” and adorn their doorways with green branches. Mothers were to braid their daughters’ hair with flowers. Sensing the joy of the day, even nursing infants would suckle more eagerly, the program stated, as old men’s eyes filled with tears and the sun beamed down. Save for the weather, it is impossible to state just how much of David’s all-inclusive program was realized that June 8. Records show, however, that the sun did shine brightly all day.

Stretching outward from the Tuileries Gardens toward the Place of the Revolution that morning, the mass of people impatiently awaited the beginning of the day’s ceremonies at noon. An amphitheatre backing onto the old machine hall of the Tuileries Palace had been especially constructed. At its base were grouped some 800 singers and instrumentalists, commandeered for the day by the government from the Paris Opera, the Conservatory of Music, and the Feydeau Theatre. Required to perform the music commissioned for the festival, both here and at the closing ceremonies at the Champ de Mars, the musicians were, for the most part, a disgruntled lot, totally lacking in any desire to join with the people of Paris in escorting the graven image of “Freedom,” the new order’s goddess, to the other side of the Seine.

By its special construction the day’s great amphitheatre allowed the representatives to enter directly on stage from their new Assembly Hall. Some 200 of them had disappeared in the spring purges, but a good 500 survivors still emerged, four by four, led by their president, Robespierre. His new and very elegant powder-blue suit contrasted sharply with their own regulation dark blue suits with red collars, but they all wore David’s regulation off-face black hats with tricolored plumes.

David’s program called upon each of Paris’s 48 municipal sections to provide 50 official representatives for the day. This horde of 2,400 he divided into five categories, each to include 10 representatives from each one of the 48 sections. The three male divisions consisted therefore of 480 boys under eight years of age, 480 adolescents between the ages of 15 and 18, and 480 old men. With the fatherland surrounded by enemies, most men of fighting age were at the front. The adolescents were therefore dressed in uniforms and armed with sabers.

There were but twο divisions of women: 480 mothers of child-bearing age and 480 nubile young women between 15 and 20 years of age. Set apart by their white dresses strikingly accented by a tricolor ribbon stretching from shoulder to waist, they differed only in what they carried: the mothers, bouquets of red roses; the maidens, baskets of flowers.

|

|

|

Preparationis for the Festival of the Supreme Being |

The first part of Robespierre’s opening speech concluded with his descent from the amphitheatre to approach the great pool of the Tuileries Gardens, covered over for the occasion with a platform. An imposing, purposely ugly papier mâché statue labelled “Atheism” dominated the middle of the platform. It was surrounded by five equally repulsive satellites: “Ambition,” “Selfishness,” “Discord,” “False Simplicity” and “Madness.” On the identifying label affixed to each satellite was also inscribed the chauvinist phrase: “The foreigner’s only hope.” According to the program, a flaming torch applied by Robespierre to the central papier mâché statue would precipitate Atheism’s immediate demise in a burst of smoke and flame. A beautiful, pristine white statue of “Wisdom,” concealed within Atheism, was to emerge from the burst of flames and receive the president’s homage in the second part of his speech.

To ensure the people’s joy in this miraculous metamorphosis, fireworks had been planted inside Atheism’s interior so as to make her fiery demise and the triumphant emergence of Wisdom as sensational and memorable as possible. Once Atheism was ignited, however, the discharging fire-works generated such excessive heat that, to the dismay of all, save Robespierre’s gloating enemies, Wisdom herself, plus four of Atheism’s five satellites, disappeared in what proved a general conflagration. Nor did the spared satellite fail to rouse appreciative sniggers from the enemy party. While a thwarted Robespierre delivered the second half of his discourse to Wisdom’s ashes, Madness looked on.

|

|

|

Burning Statues at the Festival of the Supreme Being |

Though Wisdom’s birth from the destruction of Atheism proved a fiasco, that was only the beginning of a very full day’s ceremonies. The 500-odd Convention members, each carrying David’s prescribed bouquet of wheat, flowers, and fruit, were to form an honor guard around the central float bearing the great, oversized image of Freedom. The new order’s goddess reigned majestically, seated under a full-sized Liberty Tree, her right hand resting on the small end of a huge club for crushing tyrants. From the four corners of her float, adorned with various implements of agriculture, artíficíal fruit and vegetables spilled forth from horns of plenty. David’s program also called for “eight vigorous bulls” to pull the great device. Breaking bulls to such a servile task had proven an insuperable problem, however, and eight gilded-horned oxen had to be substituted. Whatever the oxen may have lacked in the virility David admired in “vigorous bulls,” the gold of their horns shone splendidly in the bright sunshine.

The Guard of Honor for “Freedom” in turn had its own single-file honor guard enclosing them by means of a seemingly endless tricolored ribbon stretched on either side. According to the program, the twο ribbon-bearing single files were to consist of violet-crowned children, laurel-crowned adolescents, oak leaf-crowned adults, plus the elderly, the most gloriously crowned of all with headgear fashioned of olive branches and grape vines, the fruit hanging down to signífy “venerable fecundity.” An eyewitness, however, insists that, David’s program notwithstanding, street girls were actually hired at the last minute and dressed up in white to fulfill this ribbon-bearing function.

David’s program also called for a detachment of cavalry, preceded by its own trumpeters, as well as three military bands, a hundred drummers, students from the National Institute of Music, firemen, gunners, the 2,400 section representatíves in their five categories, plus formations of men and women in companies placed before and after Freedom’s float. Even students from the National Institute of the Blind were to sing a hymn to the Supreme Being, riding on their own float.

Whatever may have been David’s success in realizing all these details, a vast sea of people in official and unofficial attíre did escort the graven image of the new order’s goddess across the Seine that day. Just prior to crossing the river, however, there was a stop for a ceremony at the Place of the Revolutíon before that plaster image of Freedom to which Madame Roland had addressed her final exclamation the previous November. It was in fact the first time in 13 months that one could comfortably stop there since, overnight, all signs of the guillotine had disappeared. Robespierre thus solemnly offered incense to the goddess, conveniently separated from her guillotine, then made another speech. Finally, once across the Seine, there was another stop at the Place des Invalides. There Robespierre spoke at yet another ceremony before yet another plaster statue, this time that of “The French People.”

But the grand climax of the day transpired at the Champs-de-Mars. There, rising to 100 feet at its crest, a vast, 500-foot-wide mountain-shaped stage had been constructed to honor the triumphant “Mountain” party. Crowned with a Liberty Tree and a tall pillar, its papier mâché shell included romantic grottos, stairways, and tombs, with tripods and other geometric ornaments reflecting the republican mystique. A witness reports that due to the stage’s numerous esthetic features it actually could not accommodate more than some 200 of the representatives nearest Robespierre. They followed him as he climbed up to the top of the “mountain” to deliver his final presidential address of the day from the balcony under the Liberty Tree.

|

|

|

Concluding Ceremonies at the Festival of the Supreme Being |

The remaining 300-odd representatives were left below to fume over the president’s demagoguery. It was, however, with the clenched teeth and unhappy countenances of the commandeered musicians down at the mountain’s base that the smiles of Robespierre’s companions atop the summit contrasted the most sharply, their hats’ tricolored plumes billowing away in celebratory splendor. Impatient to get on with the music ending the long, hot day’s proceedings, the musicians below irritably awaited the grand finale.

This was to be a gestured rendition of the stanza closing the day’s final hymn to the Supreme Being. The words were by Marie Joseph Chénier, brother of the ill-fated poet André, guillotined on July 25, just twο days before Robespierre’s fall. Groups chosen from the 2,400 Parisian section representatives were placed on the mountain between the members of the Convention at the top and the musicians at the base. With mothers, young boys, and maidens situated on one side, and with adolescent youths and old men on the other, each group was to make grand theatrical gestures during the singing of the last stanza of Chénier’s text where specific little phrases were to trigger each grand gesture. Thus one saw adolescent “warriors” draw their sabers while, perched above them, the old men raised an arm in blessing. Mothers, discarding their rose bouquets, suddenly seized one of the little boys and hoisted him aloft, offering him to the “Author of Nature” while the contents of the maidens’ flower baskets showered down on them from above.

Whatever synchronization may have lacked on the mountain between the gestures and the text, compensation was found in the very enthusiastic singing of the hymn’s refrain by the people massed below them. Practiced for days in institutions and by civic groups throughout Paris, the refrain’s twο alexandrine verses were zealously sung again and again.

Before we all lay down our conqu’ring

swords sublime,

Let’s now all swear the end of tyranny and crime!

Trumpet blares unfailingly signaled the return of the familiar refrain after each stanza while the conscripted singers strained wearily to lead yet another, still louder, rendition of its militant lines. Suddenly, as all sang one last time of ending tyranny and crime, the boom of cannon fire resounded throughout Paris, crowning Robespierre’s finest day.

AS surprising as it may seem, the guillotine had not been removed from the Place of the Revolution the night before from any human scruples. Rather was it from fear that the gilded-horned oxen drawing Freedom’s float might, like horses, prove recalcitrant at the smell of blood. The organizers were haunted by a nagging fear that these dumb beasts, triumphantly parading the new order’s great goddess, might balk at the Place of the Revolution.

David and his committee knew full well that many of those 500 survivors of the purges in the National Convention were totally against the whole idea of a Supreme Being to begin with. Thus, even the slightest possibility that Robespierre’s enemies, framed in by tricolored ribbons, might be stranded in the midst of the Place of the Revolution while snorting oxen pawed the earth, wild-eyed, and Freedom’s progress came to a halt, was completely inadmissible. To guarantee the tranquil passage of the oxen, therefore, David and his committee not only had the guillotine removed, but also had workmen carefully cover over the blood-impregnated soil with thick layers of sand during the night.

As June 8 dawned, no hint remained at the Place of the Revolution of the strange but harsh daily reality of the times: blood sacrifice, human religion’s immemorial rite, was thriving in revolutionary Paris and proved itself the mystical keystone for constructing the new order with its idealism and childlike faith in human nature.

Nor was the veritable cult growing up around the guillotine the only manifestation of this strange truth. Its admissibility was publicly confirmed at the Place of the Revolution by Robespierre when he offered incense to the new order’s goddess, Freedom, there where she actually presided over the Revolution’s mechanized altar. In repeated, almost desperate dally oblations, effusions of human blood were spilled before her, nine days out of ten, to guarantee her triumph if not actually to placate her. Madame Roland, Girondin partisan and revolutionary hostess, had not at all been misled in addressing her final, despairing cry to the new order’s goddess. The revolting work of the guillotine had become generally accepted as one of the features of the new order over the past 13 months. For those so inclined it provided an assured patriotic spectacle nine days out of ten. Sanson and his valets, faced each day with the necessity of coping with a fresh and ever-swelling “batch” of victims from Fouquier-Tinville’s Revolutionary Tribunal, had long since given up dismantling the scaffold each evening. The day’s work finished, the executioners simply washed down the machine with water, removed its great triangular blade, and reported to Fouquier-Tinville to learn the number of tumbrels needed for the morrow’s “batch.”

For the residents of the fashionable neighborhood bordering the elegant ex-Place Louis XV, there was grave concern about the quantity of blood accumulating there. Hastily a grill had been erected under the machine to prevent dogs from licking each day’s effusion. But, as the months passed, the soil around the scaffold had become so saturated that those walking over it left brownish footprints on adjoining sidewalks.

Inevitably, the whole of the chic rue Saint Honoré was affected. Shopkeepers took to closing down in the afternoon to avoid exposure to the daily procession of the condemned. Several tumbrels were now needed to transport the daily “batch.” Soldiers, both mounted and on foot, plus a mass of unsavory rabble accompanied them, far outnumbering odd friends or rare relatives in the procession where degenerate women known as the “furies of the guillotine” figured prominently. Gloating over gore, mutílatíons, and massacres, and, during mob disorders, occasionally even given to cannibal ism, these “furies” invariably aimed gallows humor and obscenities at the hapless condemned.

Equally offensive to the inhabitants of that elegant district of Paris was the reddish traίl left each evening by the red-painted cart transporting the decapitated bodies to the common burial pit in a cemetery near the Church of the Madeleine. But the worst offense was the indescribable putrefying smell emanating at all hours of the day and night from the scaffold site. Before the guillotine’s June 8 removal the intense heat of early June had already begun to accentuate it. The state of what so shortly before had been western Europe’s most luminous Christian city now shocked the outside world. In the heart of the capital city of St. Louis, saved and protected by the holy prayers of St. Geneviève, there reigned the stench of putrefying human blood. It spoke far more eloquently of the profound disorder unleashed by the new order than did rites of communion at the Place de la Bastille or cults to freedom martyrs interred in the Pantheon and then removed.

Having hoped his Supreme Being would instigate a new national cult controlled by human reason, the unfortunate Robespierre inexplicably found himself ensnared in the workings of totally irrational forces. These forces revealed that human beings are, in one form or another, not only inevitably religious, but also generally prone to shedding the blood of the individual to assure the well-being of the whole. Indeed, the implacability of these perennial and mysteriously irrational forces was manifested by Marat’s cry for thousands of heads, as also by Danton’s solid conviction that still “more audacious” means were necessary to assure the Revolution’s success. Thus, as new, post-Christian France valiantly strove to banish the superstition and fanaticism of the old order, its mentors, faithful to a basic human instinct demanding religious sacrifice to assure success, publicly cried out for an ever-increasing ritual shedding of blood.

Against such forces neither Robespierre nor anyone else could do anything. The irony of fate had determined that the crude and primitive rite of human sacrifice surreptitiously creep back into French dally life with the government’s blessing. The refined, stylized, and mystical bloodless sacrifice of the Body and Blood of Jesus Christ in the now-forbidden Christian Eucharist, even though offered dally for 13 centuries in France’s thousands of churches, had now been spectacularly replaced by a more direct and less stylized sacrifice. The guillotine’s red-splattered wood and steel supplanted the immaculate white linen of the Christian altar; the stench of the place of sacrifice, the sweetness of the smoking censer. The paltry, totally irrational Christian offering to God of small tokens of bread and wine, which “fanatics” of the Crucified actually claimed became his flesh and blood and the immortal food of human souls, had finally been eclipsed. The new order, on the other hand, offered tangible proof of the progress being made by the Enlightenment, thanks to a more philosophically enlightened daily rite wherein even the mechanism for sacrifice had been devised to achieve human equality.

ON June 8, 1794, Christian Pentecost was thus replaced in France by Robespierre’s Festival of the Supreme Being. As its pagan procession, so proudly owing nothing whatsoever to France’s 13 centuries of Judeo-Christian heritage, triumphantly escorted its new goddess out of the Place of the Revolutíon and across the Seine, neither the president nor his intimates could possibly have entertained the idea that their own personal and íll-fated Pentecost had begun that very day. As if a subtle reminder of the abiding power of that God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob whose seven-day week they had scorned, they would all be brought back to this site as condemned prisoners 50 days hence and executed in the most appalling circumstances.

|

|

|

Execution of Robespierre |

More dead than alive, the humiliated Robespierre would be mocked and railed at by a vengeful mob, drunk with blood lust. His elegant powder-blue suit would be worn, dirty and bloodstained from a suicide attempt the night before, when a pistol shot had nearly detached one side of his jaw. The soiled bloodstained bandage that secured it to his face would be ripped off by Sanson as he fixed the Incorruptible’s mangled head in the neck-stall for decapitation. The resulting animal howl of pain was quelled only by the crashing blade.

Also executed in a mangled state was Robespierre’s 31-year-old younger brother. He too had attempted suicide the evening before with a leap from the Hotel de Ville, crushing his leg. But more grotesque still was the dispatch of the crippled 39-year-old Couthon. His body was so twisted by rheumatism that his lower half was totally immobile. All of Sanson’s professional ingenuity was required to twist his head into the neck-stall.

This macabre and bloody Robespierrian Pentecost marked not only 50 days after the Festival of the Supreme Being, but 100 days after the most persecuted celebration of Easter in French history. Faced with open persecution, routed and cowed French Christians had tried to celebrate, clandestinely or otherwise, the resurrection of their Lord and God, Jesus Christ On 20:17), from the dead. The grotesque events on thatJuly 28, 1794, seemed to some, therefore, a sort of ironic reply to Robespierre’s flaunting his Supreme Being on the venerable feast celebrating the birth of the church of Jesus Christ.

In any case, those final 50 days of Robespierre’s reign were characterized by great darkness throughout France. By allowing accusations to suffice as proof of guilt, the laω of 22 Prairial, passed just twο days after the great festival, unleashed the full fury of the Great Terror. It would rage, unchecked, until the Incorruptible’s fall on July 27. The Carmelites’ oblation marked the thirty-ninth day of that Robespierrian Pentecost, Robespierre’s own fall the forty-ninth.

Given the new calendar’s ten-day décade, the fiftieth day after the Festival of the Supreme Being was, of necessity, also a décadi holiday. As an exception, the guillotine functioned that décadi and, as we have just seen, in the most appalling manner, being expressly returned from the Place of the Throne to the Place of the Revolution for the execution of Robespierre and his associates. That sorry spectacle was hailed as the greatest event taking place in Paris on that re publican day of rest.

But an even sorrier spectacle took place at the same site the following day. Within the space of one hour and forty-five minutes, the Mayor of Paris and all 87 members of his city council were guillotined in a blood orgy of hallucinatory horror. Though labeled “Robespierre’s accomplices,” the only crime for most of them was their election to the municipal government by their local sections. This staggering official execution of July 29, 1794, where for almost twο hours, we are told, there was an effusion of blood every minute and a quarter, is seldom referred to by historians. An eyewitness account is still chilling to read. One recalls that human blood crept outward from the scaffold until a pool stretched 50 feet in all directions. In spite of countless bushels of bran put down by the executioner’s valets to stop its flow, before the end the condemned were slipping as they tried to climb the scaffold steps.

For almost twο years, the 16 Carmelites of Compiègne, wishing to save France and her church according to the rites of France’s old order, had daily consecrated themselves for holocaust that such works of darkness might be held at bay. And as though it were a last gasp following Robespierre’s dispatch on July 28, this final, massive hemorrhage on July 29 did in fact mark a definitive turning of the tide of official revolutíοnary blood-letting. Believers might well say that the nuns’ July 17 oblation had begun to quell the Terror.

|

|

|

The Pantheon |

This Webpage was created for a workshop held at Saint Andrew's Abbey, Valyermo, California in 2014