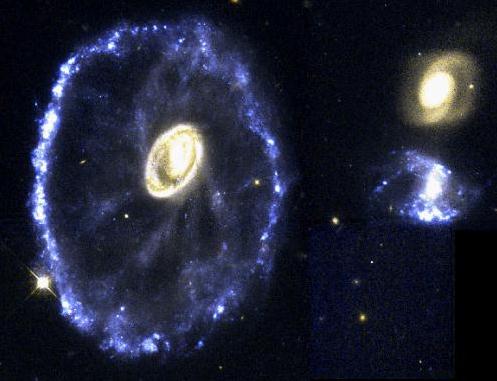

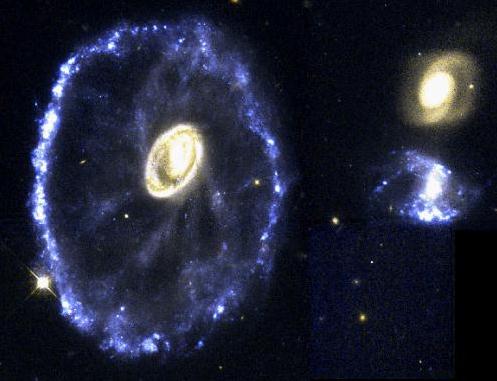

CONSCIENCE LOOKS OUT & INTERPRETS MEANING (GLORY) of GOD in A CREATION that REFLECTS GOD'S WILL:

VERITATIS SPLENDOR: Chapter 1

|

[1] Jesus Christ, the true light that enlightens everyone (§ 1-3) [»Light] [2] The purpose of the present Encyclical (§ 4-5)

CHAPTER

ONE: “TEACHER, WHAT GOOD MUST I DO ...?”

(Mt. 19:16): “Someone came to him...” (Mt 19:16) (§ 6-7) “Teacher, what good must I do to have eternal life?” (Mt 19:16) (No. 8) “There is only one who is good” (Mt 19:17) (§ 9-11) “If you wish to enter into life, keep the commandment” (Mt 19:17 (§ 12-15) “If you wish to be perfect” (Mt 19:21) (§ 12-15) “Come, follow me” (Mt 19:21) (Nos 19-21) “With God all things are possible”(Mt 19:26) (§ 22-24) [»Heart] “Lo,

I am with you always, to the close of the age” (Mt 28:20) (§ 25-27) |

Venerable Brothers in the Episcopate, Health and the Apostolic Blessing!

The

Splendour of

Truth shines forth in all the works of the Creator and, in a

special way, in man, created in the image and likeness of God (cf. Gen 1:26).

Truth enlightens man’s intelligence and shapes his freedom, leading him to

know and love the Lord. Hence the Psalmist prays: “Let the light of your face

shine on us, O Lord” (Ps 4:6).

INTRODUCTION: [»cont.]

[1] JESUS CHRIST, THE TRUE LIGHT THAT ENLIGHTENS EVERYONE

|

Why the emphasis on “light” in this encyclical? St.

Irenaeus of Lyons |

|

For just as those who see the light are within the light and participate in its splendor, even so, those who see God are within God and participate in His splendor. And His splendor gives them life: those, therefore, who see God participate in life. And for this reason, He who is beyond our capacity, incomprehensible, and invisible, makes himself visible, comprehensible, and within the capacity of those who believe, in order to give life to those who participate in and behold Him through faith. |

Gr. frg.10 pp. 640-642 Ὥσπερ οἱ βλέποντες τὸ φῶς ἐντός εἰσι τοῦ φωτὸς καὶ τῆς λαμπρότητος αὐτοῦ μετέχουσιν, οὕτως οἱ βλέποντες τὸν Θεὸν ἐντός εἰσι τοῦ Θεοῦ, μετέχοντες αὐτοῦ τῆς λαμπρότητος· ζωῆς οὖν μετέξ-ουσιν οἱ ὁρῶντες Θεόν. Καὶ διὰ τοῦτο ὁ ἀχώρητος καὶ ἀκατάληπτος καὶ ἀόρατος ὁρώμενον ἑαυτὸν καὶ καταλαμβανόμενον καὶ χωρούμενον τοῖς πιστοῖς παρέσχεν, ἵνα ζωοποιήσῃ τοὺς χωροῦντας καὶ βλέποντας αὐτὸν διὰ πίστεως. |

|

Quemadmodum enim videntes lumen intra lumen sunt et claritatem ejus percipiunt, sic et qui vident Deum intra Deum sunt, percipientes ejus claritatem. Vivificat autem Dei claritas : I percipiunt ergo vitam qui vident Deum. Et propter hoc incapabilis et incomprehensibilis <et invisibilis > visibilem se et comprehensibilem et capacem hominibus praestat, ut vivificet percipientes et videntes se. |

|

For just as His grandeur is unfathomable, so also His gentle mercy is inexpressible; by which, having been seen, He bestows life on those who see Him. It is not possible to live separated from life, and the means of life is found in fellowship with God; but fellowship with God is to know God, and to take pleasure in His gentle mercy. [goodness] |

Ὡς γὰρ τὸ μέγεθος αὐτοῦ ἀνεξιχνίαστον, οὕτως καὶ ἡ ἀγαθότης αὐτοῦ ἀνεξήγητος, δι' ἧς βλεπόμενος ζωὴν ἐνδίδωσι τοῖς ὁρῶσιν αὐτόν. Ἐπεὶ ζῆσαι ἄνευ ζωῆς οὐχ οἷόν τε ἦν, ἡ δὲ ὕπαρξις τῆς ζωῆς ἐκ τῆς τοῦ Θεοῦ περιγίνεται μετοχῆς, μετοχὴ δὲ Θεοῦ ἐστι τὸ γινώσκειν Θεὸν καὶ ἀπολαύειν τῆς χρηστότητος αὐτοῦ. |

|

Quemadmodum enim magnitudo ejus investigabilis, sic et benignitas ejus inenarrabilis, per quam visus vitam praestat his qui vident eum : quoniam vivere sine vita impossibile est, subsistentia autem vitae de Dei participatione evenit, participatio autem Dei est videre Deum et frui benignitate ejus. |

|

6. Human beings shall therefore see God in order to live, being made immortal by that sight and even entering into God. . . |

20, 6. Homines igitur videbunt Deum ut vivant, per visionem immortales facti et pertingentes usque in Deum. |

|

gloria

enim Dei

|

[»Light] [»Heart] [» Unity Faith & Morals]

|

The Effects of Original Sin on Moral Conscience: |

CALLED to salvation through faith in Jesus Christ “the true light that enlightens everyone” (Jn 1:9), people become “light in the Lord” and “children of light” (Eph 5:8), and are made holy by “obedience to the truth” (1 Pet 1:22).

This obedience is not always easy. As a result of that mysterious original sin, committed at the prompting of Satan, the one who is “a liar and the father of lies” (Jn 8:44),[:]

[1] man is constantly tempted to turn his [contemplative] gaze away from the living and true God in order to direct it towards idols (cf.1 Thes 1:9),

[2] exchanging “the truth about God for a lie” (Rom 1:25). Man’s capacity to know the truth is also darkened,

[3] and his will to submit to it is weakened.

Thus, giving himself over to relativism and scepticism (cf. Jn 18:38), he goes off in search of an illusory freedom apart from truth itself.

[»Light] [»Heart] [» Unity Faith & Morals]

But no darkness of error or of sin can totally take away from man the light of God the Creator. In the depths of his heart there always remains a yearning for absolute truth and a thirst to attain full knowledge of it. This is eloquently proved by man’s tireless search for knowledge in all fields. It is proved even more by his search for “the meaning of life.” The development of science and technology, this splendid testimony of the human capacity for understanding and for perseverance, does not free humanity from the obligation to ask the ultimate religious questions. Rather, it spurs us on to face the most painful and decisive of struggles, those of the heart and of the moral conscience.

2.

No one can escape from the fundamental questions: “What must I do? How do I

distinguish good from evil?” The answer is only possible thanks to the

splendour of the truth which shines forth deep within the human spirit, as the

Psalmist bears witness: “There are many who say: ‘O that we might see some

good! Let the light of your face shine on us, O Lord”‘

(Ps 4:6).

The light of God’s face shines in all its beauty on the countenance of Jesus Christ, “the image of the invisible God” (Col 1:15), the “reflection of God’s glory” (Heb 1:3), “full of grace and truth” (Jn 1:14). Christ is “the way, and the truth, and the life” (Jn 14:6). Consequently the decisive answer to every one of man’s questions, his religious and moral questions in particular, is given by Jesus Christ, or rather is Jesus Christ himself, as the Second Vatican Council recalls: “In fact, ‘it is only in the mystery of the Word incarnate that light is shed on the mystery of man.’ For Adam, the first man, was a figure of the future man, namely, of Christ the Lord. It is Christ, the last Adam, who fully discloses man to himself and unfolds his noble calling by revealing the mystery of the Father and the Father’s love”.[1]

Jesus

Christ, the “light of the nations”, shines upon the face of his Church,

which he sends forth to the whole world to proclaim the Gospel to every creature

(cf. Mk 16:15).[2] Hence the Church, as the People of God among the nations,[3]

while attentive to the new challenges of history and to mankind’s efforts to

discover the meaning of life, offers to everyone the answer which comes from the

truth about Jesus Christ and his Gospel. The Church remains deeply conscious of

her “duty in every age of examining the signs of the times and interpreting

them in the light of the Gospel, so that she can offer in a manner appropriate

to each generation replies to the continual human questionings on the meaning of

this life and the life to come and on how they are related”.[4]

3.

The Church’s Pastors, in communion with the Successor of Peter, are close to

the faithful in this effort; they guide and accompany them by their

authoritative teaching, finding ever new ways of speaking with love and mercy

not only to believers but to all people of good will. The Second Vatican Council

remains an extraordinary witness of this attitude on the part of the Church

which, as an “expert in humanity”,[5] places herself at the service of every

individual and of the whole world.[6]

The

Church knows that the issue of morality is one which deeply touches every

person; it involves all people, even those who do not know Christ and his Gospel

or God himself. She knows that it is precisely “on the path of the moral life

that the way of salvation is open to all.” The Second Vatican Council clearly

recalled this when it stated that “those who without any fault do not know

anything about Christ or his Church, yet who search for God with a sincere heart

and under the influence of grace, try to put into effect the will of God as

known to them through the dictate of conscience... can obtain eternal

salvation”. The Council added: “Nor does divine Providence deny the helps

that are necessary for salvation to those who, through no fault of their own

have not yet attained to the express recognition of God, yet who strive, not

without divine grace, to lead an upright life. For whatever goodness and truth

is found in them is considered by the Church as a preparation for the Gospel and

bestowed by him who enlightens everyone that they may in the end have

life”.[7]

THE

PURPOSE OF THE PRESENT ENCYCLICAL

4.

At all times, but particularly in the last two centuries, the Popes, whether

individually or together with the College of Bishops, have developed and

proposed a moral teaching regarding the “many different spheres of human

life.” In Christ’s name and with his authority they have exhorted, passed

judgment and explained. In their efforts on behalf of humanity, in fidelity to

their mission, they have confirmed, supported and consoled. With the guarantee

of assistance from the Spirit of truth they have contributed to a better

understanding of moral demands in the areas of human sexuality, the family, and

social, economic and political life. In the tradition of the Church and in the

history of humanity, their teaching represents a constant deepening of knowledge

with regard to morality.[8]

Today,

however, it seems “necessary to reflect on the whole of the Church’s moral

teaching,” with the precise goal of recalling certain fundamental truths of

Catholic doctrine which, in the present circumstances, risk being distorted or

denied. In fact, a new situation has come about “within the Christian

community itself,” which has experienced the spread of numerous doubts and

objections of a human and psychological, social and cultural, religious and even

properly theological nature, with regard to the Church’s moral teachings. It

is no longer a matter of limited and occasional dissent, but of an overall and

systematic calling into question of traditional moral doctrine, on the basis of

certain anthropological and ethical presuppositions. At the root of these

presuppositions is the more or less obvious influence of currents of thought

which end by detaching human freedom from its essential and constitutive

relationship to truth. Thus the traditional doctrine regarding the natural law,

and the universality and the permanent validity of its precepts, is rejected;

certain of the Church’s moral teachings are found simply unacceptable; and the

Magisterium itself is considered capable of intervening in matters of morality

only in order to “exhort consciences” and to “propose values”, in the

light of which each individual will independently make his or her decisions and

life choices.

In

particular, note should be taken of the “lack of harmony between the

traditional response of the Church and certain theological positions,”

encountered even in Seminaries and in Faculties of Theology, “with regard to

questions of the greatest importance” for the Church and for the life of faith

of Christians, as well as for the life of society itself. In particular, the

question is asked: do the commandments of God, which are written on the human

heart and are part of the Covenant, really have the capacity to clarify the

daily decisions of individuals and entire societies? Is it possible to obey God

and thus love God and neighbour, without respecting these commandments in all

circumstances? Also, an opinion is frequently heard which questions the

intrinsic and unbreakable bond between faith and morality, as if membership in

the Church and her internal unity were to be decided on the basis of faith

alone, while in the sphere of morality a pluralism of opinions and of kinds of

behaviour could be tolerated, these being left to the judgment of the individual

subjective conscience or to the diversity of social and cultural contexts.

5.

Given these circumstances, which still exist, I came to the decision--as I

announced in my Apostolic Letter “Spiritus Domini” issued on 1 August 1987

on the second centenary of the death of Saint Alphonsus Maria de’ Liguori--to

write an Encyclical with the aim of treating “more fully and more deeply the

issues regarding the very foundations of moral theology”,[9] foundations which

are being undermined by certain present day tendencies.

I

address myself to you, Venerable Brothers in the Episcopate, who share with me

the responsibility of safeguarding “sound teaching” (2 Tim 4:3), with the

intention of “clearly setting forth certain aspects of doctrine which are of

crucial importance in facing what is certainly a genuine crisis,” since the

difficulties which it engenders have most serious implications for the moral

life of the faithful and for communion in the Church, as well as for a just and

fraternal social life.

If

this Encyclical, so long awaited, is being published only now, one of the

reasons is that it seemed fitting for it to be preceded by the “Catechism of

the Catholic Church,” which contains a complete and systematic exposition of

Christian moral teaching. The Catechism presents the moral life of believers in

its fundamental elements and in its many aspects as the life of the “children

of God”: “Recognizing in the faith their new dignity, Christians are called

to lead henceforth a life ‘worthy of the Gospel of Christ’ (Phil 1:27).

Through the sacraments and prayer they receive the grace of Christ and the gifts

of his Spirit which make them capable of such a life”.[10]

Consequently, while referring back to the Catechism “as a sure and authentic reference text for teaching Catholic doctrine”,[11] the Encyclical will limit itself to dealing with “certain fundamental questions regarding the Church’s moral teaching,” taking the form of a necessary discernment about issues being debated by ethicists and moral theologians. The specific purpose of the present Encyclical is this: to set forth, with regard to the problems being discussed, the principles of a moral teaching based upon Sacred Scripture and the living Apostolic Tradition,[12] and at the same time to shed light on the presuppositions and consequences of the dissent which that teaching has met.

“Teacher,

what good must I do...?”

(Mt 19:16).

CHRIST and the ANSWER to the QUESTION ABOUT MORALITY

“Someone

came to him...”

(Mt 19:16)

6.

“The dialogue of Jesus with the rich young man,” related in the nineteenth

chapter of Saint Matthew’s Gospel, can serve as a useful guide “for

listening once more” in a lively and direct way to his moral teaching: “Then

someone came to him and said, ‘Teacher, what good must I do to have eternal

life?’ And he said to him, ‘Why do you ask me about what is good? There is

only one who is good. If you wish to enter into life, keep the commandments.’

He said to him, ‘Which ones?’ And Jesus said, ‘You shall not murder; You

shall not commit adultery; You shall not steal; You shall not bear false

witness; Honour your father and mother; also, You shall love your neighbour as

yourself.’ The young man said to him, ‘I have kept all these; what do I

still lack?’ Jesus said to him, ‘If you wish to be perfect, go, sell your

possessions and give the money to the poor, and you will have treasure in

heaven; then come, follow me’“

(Mt 19:16-21).[13]

7.

“Then someone came to him. . .”. In the young man, whom Matthew’s Gospel

does not name, we can recognize every person who, consciously or not,

“approaches Christ the Redeemer of man and questions him about morality.”

For the young man, the “question” is not so much about rules to be followed,

but “about the full meaning of life.” This is in fact the aspiration at the

heart of every human decision and action, the quiet searching and interior

prompting which sets freedom in motion. This question is ultimately an appeal to

the absolute Good which attracts us and beckons us; it is the echo of a call

from God who is the origin and goal of man’s life. Precisely in this

perspective the Second Vatican Council called for a renewal of moral theology,

so that its teaching would display the lofty vocation which the faithful have

received in Christ,[14] the only response fully capable of satisfying the desire

of the human heart.

“In

order to make this ‘encounter’ with Christ possible, God willed his

Church.” Indeed, the Church “wishes to serve this single end: that each

person may be able to find Christ, in order that Christ may walk with each

person the path of life.”[15]

“Teacher,

what good must I do to have eternal life?”

(Mt 19:16)

8.

The question which the rich young man puts to Jesus of Nazareth is one which

rises from the depths of his heart. It is “an essential and unavoidable

question for the life of every man,” for it is about the moral good which must

be done, and about eternal life. The young man senses that there is a connection

between moral good and the fulfilment of his own destiny. He is a devout

Israelite, raised as it were in the shadow of the Law of the Lord. If he asks

Jesus this question, we can presume that it is not because he is ignorant of the

answer contained in the Law. It is more likely that the attractiveness of the

person of Jesus had prompted within him new questions about moral good. He feels

the need to draw near to the One who had begun his preaching with this new and

decisive proclamation: “The time is fulfilled, and the Kingdom of God is at

hand; repent, and believe in the Gospel” (Mk 1:15).

“People

today need to turn to Christ once again in order to receive from him the answer

to their questions about what is good and what is evil.” Christ is the

Teacher, the Risen One who has life in himself and who is always present in his

Church and in the world. It is he who opens up to the faithful the book of the

Scriptures and, by fully revealing the Father’s will, teaches the truth about

moral action. At the source and summit of the economy of salvation, as the Alpha

and the Omega of human history (cf. Rev 1:8; 21:6; 22:13), Christ sheds light on

man’s condition and his integral vocation. Consequently, “the man who wishes

to understand himself thoroughly--and not just in accordance with immediate,

partial, often superficial, and even illusory standards and measures of his

being--must with his unrest, uncertainty and even his weakness and sinfulness,

with his life and death, draw near to Christ. He must, so to speak, enter him

with all his own self; he must ‘appropriate’ and assimilate the whole of the

reality of the Incarnation and Redemption in order to find himself. If this

profound process takes place within him, he then bears fruit not only of

adoration of God but also of deeper wonder at himself”.[16]

If

we therefore wish to go to the heart of the Gospel’s moral teaching and grasp

its profound and unchanging content, we must carefully inquire into the meaning

of the question asked by the rich young man in the Gospel and, even more, the

meaning of Jesus’ reply, allowing ourselves to be guided by him. Jesus, as a

patient and sensitive teacher, answers the young man by taking him, as it were,

by the hand, and leading him step by step to the full truth.

“There

is only one who is good” (Mt 19:17)

9.

Jesus says: “Why do you ask me about what is good? There is only one who is

good. If you wish to enter into life, keep the commandments” (Mt 19:17). In

the versions of the Evangelists Mark and Luke the question is phrased in this

way: “Why do you call me good? No one is good but God alone” (Mk 10:18; cf.

Lk 18:19).

Before

answering the question, Jesus wishes the young man to have a clear idea of why

he asked his question. The “Good Teacher” points out to him--and to all of

us--that the answer to the question, “What good must I do to have eternal

life?” can only be found by turning one’s mind and heart to the “One”

who is good: “No one is good but God alone” (Mk 10:18; cf. Lk 18:19).

“Only God can answer the question about what is good, because he is the Good

itself.”

“To

ask about the good,” in fact, “ultimately means to turn towards God,” the

fullness of goodness. Jesus shows that the young man’s question is really a

“religious question, and that the goodness that attracts and at the same time

obliges man has its source in God, and indeed is God himself. God alone is

worthy of being loved “with all one’s heart, and with all one’s soul, and

with all one’s mind” (Mt 22:37). He is the source of man’s happiness.

Jesus brings the question about morally good action back to its religious

foundations, to the acknowledgment of God, who alone is goodness, fullness of

life, the final end of human activity, and perfect happiness.

10.

The Church, instructed by the Teacher’s words, believes that man, made in the

image of the Creator, redeemed by the Blood of Christ and made holy by the

presence of the Holy Spirit, has as the “ultimate purpose” of his life to

“live ‘for the praise of God’s glory’“ (cf. Eph 1:12), striving to

make each of his actions reflect the splendour of that glory. “Know, then, O

beautiful soul, that you are “the image of God”,” writes Saint Ambrose.

“Know that you are “the glory of God” (1 Cor 11:7). Hear how you are his

glory. The Prophet says: “Your knowledge has become too wonderful for me”

(cf. Ps. 138:6, Vulg.). That is to say, in my work your majesty has become more

wonderful; in the counsels of men your wisdom is exalted. When I consider

myself, such as I am known to you in my secret thoughts and deepest emotions,

the mysteries of your knowledge are disclosed to me. Know then, O man, your

greatness, and be vigilant”.[17]

“What

man is and what he must do becomes clear as soon as God reveals himself.” The

Decalogue is based on these words: “I am the Lord your God, who brought you

out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of bondage” (Ex 20:2-3). In the

“ten words” of the Covenant with Israel, and in the whole Law, God makes

himself known and acknowledged as the One who “alone is good”; the One who

despite man’s sin remains the “model” for moral action, in accordance with

his command, “You shall be holy; for I the Lord your God am holy” (Lev

19:2); as the One who, faithful to his love for man, gives him his Law (cf. Ex

19:9-24 and 20:18-21) in order to restore man’s original and peaceful harmony

with the Creator and with all creation, and, what is more, to draw him into his

divine love: “I will walk among you, and will be your God, and you shall be my

people” (Lev 26:12).

“The

moral life presents itself as the response” due to the many gratuitous

initiatives taken by God out of love for man. It is a response of love,

according to the statement made in Deuteronomy about the fundamental

commandment: “Hear, O Israel: The Lord our God is one Lord; and you shall love

the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your

might. And these words which I command you this day shall be upon your heart;

and you shall teach them diligently to your children” (Dt 6:4-7). Thus the

moral life, caught up in the gratuitousness of God’s love, is called to

reflect his glory: “For the one who loves God it is enough to be pleasing to

the One whom he loves: for no greater reward should be sought than that love

itself; charity in fact is of God in such a way that God himself is

charity”.[18]

11.

The statement that “There is only one who is good” thus brings us back to

the “first tablet” of the commandments, which calls us to acknowledge God as

the one Lord of all and to worship him alone for his infinite holiness (cf. Ex

20:2-11). “The good is belonging to God, obeying him,” walking humbly with

him in doing justice and in loving kindness (cf. Mic 6:8). “Acknowledging the

Lord as God is the very core, the heart of the Law, from which the particular

precepts flow and towards which they are ordered. In the morality of the

commandments the fact that the people of Israel belongs to the Lord is made

evident, because God alone is the One who is good. Such is the witness of Sacred

Scripture, imbued in every one of its pages with a lively perception of God’s

absolute holiness: “Holy, holy, holy is the Lord of hosts” (Is 6:3).

But

if God alone is the Good, no human effort, not even the most rigorous observance

of the commandments, succeeds in “fulfilling” the Law, that is,

acknowledging the Lord as God and rendering him the worship due to him alone

(cf. Mt 4:10). “This ‘fulfilment’ can come only from a gift of God:” the

offer of a share in the divine Goodness revealed and communicated in Jesus, the

one whom the rich young man addresses with the words “Good Teacher” (Mk

10:17; Lk 18:18). What the young man now perhaps only dimly perceives will in

the end be fully revealed by Jesus himself in the invitation: “Come, follow

me” (Mt 19:21).

“If

you wish to enter into life, keep the commandments” (Mt 19:17)

12.

Only God can answer the question about the good, because he is the Good. But God

has already given an answer to this question: he did so “by creating man and

ordering him” with wisdom and love to his final end, through the law which is

inscribed in his heart (cf. Rom 2:15), the “natural law”. The latter “is

nothing other than the light of understanding infused in us by God, whereby we

understand what must be done and what must be avoided. God gave this light and

this law to man at creation”.[19] He also did so “in the history of

Israel,” particularly in the “ten words”, the “commandments of Sinai,”

whereby he brought into existence the people of the Covenant (cf. Ex 24) and

called them to be his “own possession among all peoples”, “a holy

nation” (Ex 19:5-6), which would radiate his holiness to all peoples (cf. Wis

18:4; Ez 20:41). The gift of the Decalogue was a promise and sign of the “New

Covenant,” in which the law would be written in a new and definitive way upon

the human heart (cf. Jer 31:31-34), replacing the law of sin which had

disfigured that heart (cf. Jer 17:1). In those days, “a new heart” would be

given, for in it would dwell “a new spirit”, the Spirit of God (cf. Ez

36:24-28).[20]

Consequently,

after making the important clarification: “There is only one who is good”,

Jesus tells the young man: “If you wish to enter into life, keep the

commandments” (Mt 19:17). In this way, a dose connection is made “between

eternal life and obedience to God’s commandments:” God’s commandments show

man the path of life and they lead to it. From the very lips of Jesus, the new

Moses, man is once again given the commandments of the Decalogue. Jesus himself

definitively confirms them and proposes them to us as the way and condition of

salvation. “The commandments are linked to a promise.” In the Old Covenant

the object of the promise was the possession of a land where the people would be

able to live in freedom and in accordance with righteousness (cf. Dt 6:20-25).

In the New Covenant the object of the promise is the “Kingdom of Heaven”, as

Jesus declares at the beginning of the “Sermon on the Mount”--a sermon which

contains the fullest and most complete formulation of the New Law (cf. Mt 5-7),

clearly linked to the Decalogue entrusted by God to Moses on Mount Sinai. This

same reality of the Kingdom is referred to in the expression “eternal life”,

which is a participation in the very life of God. It is attained in its

perfection only after death, but in faith it is even now a light of truth, a

source of meaning for life, an inchoate share in the full following of Christ.

Indeed, Jesus says to his disciples after speaking to the rich young man:

“Every one who has left houses or brothers or sisters or father or mother or

children or lands, for my name’s sake, will receive a hundredfold and inherit

eternal life” (Mt 19:29).

13.

Jesus’ answer is not enough for the young man, who continues by asking the

Teacher about the commandments which must be kept: “He said to him, ‘Which

ones?”‘ (Mt 19:18). He asks what he must do in life in order to show that he

acknowledges God’s holiness. After directing the young man’s gaze towards

God, Jesus reminds him of the commandments of the Decalogue regarding one’s

neighbour: “Jesus said: ‘You shall not murder; You shall not commit

adultery; You shall not bear false witness; Honour your father and mother; also,

You shall love your neighbour as yourself “ (Mt 19:18-19).

From

the context of the conversation, and especially from a comparison of Matthew’s

text with the parallel passages in Mark and Luke, it is clear that Jesus does

not intend to list each and every one of the commandments required in order to

“enter into life”, but rather wishes to draw the young man’s attention to

the “‘centrality’ of the Decalogue” with regard to every other precept,

inasmuch as it is the interpretation of what the words “I am the Lord your

God” mean for man. Nevertheless we cannot fail to notice which commandments of

the Law the Lord recalls to the young man. They are some of the commandments

belonging to the so-called “second tablet” of the Decalogue, the summary

(cf. Rom 13:8-10) and foundation of which is “the commandment of love of

neighbour:” “You shall love your neighbour as yourself” (Mt 19:19; cf. Mk

12:31). In this commandment we find a precise expression of “the singular

dignity of the human person,” “the only creature that God has wanted for its

own sake”.[21] The different commandments of the Decalogue are really only so

many reflections of the one commandment about the good of the person, at the

level of the many different goods which characterize his identity as a spiritual

and bodily being in relationship with God, with his neighbour and with the

material world. As we read in the “Catechism of the Catholic Church,” “the

Ten Commandments are part of God’s Revelation. At the same time, they teach us

man’s true humanity. They shed light on the essential duties, and so

indirectly on the fundamental rights, inherent in the nature of the human

person”.[22]

The

commandments of which Jesus reminds the young man are meant to safeguard “the

good” of the person, the image of God, by protecting his “goods.” “You

shall not murder; You shall not commit adultery; You shall not steal; You shall

not bear false witness” are moral rules formulated in terms of prohibitions.

These negative precepts express with particular force the ever urgent need to

protect human life, the communion of persons in marriage, private property,

truthfulness and people’s good name.

The

commandments thus represent the basic condition for love of neighbour; at the

same time they are the proof of that love. They are the “first necessary step

on the journey towards freedom,” its starting-point. “The beginning of

freedom”, Saint Augustine writes, “is to be free from crimes... such as

murder, adultery, fornication, theft, fraud, sacrilege and so forth. When once

one is without these crimes (and every Christian should be without them), one

begins to lift up one’s head towards freedom. But this is only the beginning

of freedom, not perfect freedom...”.[23]

14.

This certainly does not mean that Christ wishes to put the love of neighbour

higher than, or even to set it apart from, the love of God. This is evident from

his conversation with the teacher of the Law, who asked him a question very much

like the one asked by the young man. Jesus refers him to “the two commandments

of love of God and love of neighbour” (cf. Lk 10:25-27), and reminds him that

only by observing them will he have eternal life: “Do this, and you will

live” (Lk 10:28). Nonetheless it is significant that it is precisely the

second of these commandments which arouses the curiosity of the teacher of the

Law, who asks him: “And who is my neighbour?” (Lk 10:29). The Teacher

replies with the parable of the Good Samaritan, which is critical for fully

understanding the commandment of love of neighbour (cf. Lk 10:30-37).

These

two commandments, on which “depend all the Law and the Prophets” (Mt 22:40),

are profoundly connected and mutually related. Their inseparable unity is

attested to by Christ in his words and by his very life: his mission culminates

in the Cross of our Redemption (cf. Jn 3:14-15), the sign of his indivisible

love for the Father and for humanity (cf. Jn 13:1).

Both

the Old and the New Testaments explicitly affirm that “without love of

neighbour,” made concrete in keeping the commandments, “genuine love for God

is not possible.” Saint John makes the point with extraordinary forcefulness:

“If anyone says, ‘I love God’, and hates his brother, he is a liar; for he

who does not love his brother whom he has seen, cannot love God whom he has not

seen” (1 Jn 4:20). The Evangelist echoes the moral preaching of Christ,

expressed in a wonderful and unambiguous way in the parable of the Good

Samaritan (cf. Lk 10:30-37) and in his words about the final judgment (cf. Mt

25:31-46).

15.

In the “Sermon on the Mount”, the “magna charta” of Gospel morality,[24]

Jesus says: “Do not think that I have come to abolish the Law and the

Prophets; I have come not to abolish them but to fulfil them” (Mt 5:17).

Christ is the key to the Scriptures: “You search the Scriptures...; and it is

they that bear witness to me” (Jn 5:39). Christ is the centre of the economy

of salvation, the recapitulation of the Old and New Testaments, of the promises

of the Law and of their fulfilment in the Gospel; he is the living and eternal

link between the Old and the New Covenants. Commenting on Paul’s statement

that “Christ is the end of the law” (Rom 10:4), Saint Ambrose writes: “end

not in the sense of a deficiency, but in the sense of the fullness of the Law: a

fullness which is achieved in Christ (“plenitudo legis in Christo est”),

since he came not to abolish the Law but to bring it to fulfilment. In the same

way that there is an Old Testament, but all truth is in the New Testament, so it

is for the Law: what was given through Moses is a figure of the true law.

Therefore, the Mosaic Law is an image of the truth”.[25]

“Jesus

brings God’s commandments to fulfilment,” particularly the commandment of

love of neighbour, “by interiorizing their demands and by bringing out their

fullest meaning.” Love of neighbour springs from “a loving heart” which,

precisely because it loves, is ready to live out “the loftiest challenges.”

Jesus shows that the commandments must not be understood as a minimum limit not

to be gone beyond, but rather as a path involving a moral and spiritual journey

towards perfection, at the heart of which is love (cf. Col 3:14). Thus the

commandment “You shall not murder” becomes a call to an attentive love which

protects and promotes the life of one’s neighbour. The precept prohibiting

adultery becomes an invitation to a pure way of looking at others, capable of

respecting the spousal meaning of the body: “You have heard that it was said

to the men of old, ‘You shall not kill; and whoever kills shall be liable to

judgment’. But I say to you that every one who is angry with his brother shall

be liable to judgment... You have heard that it was said, ‘You shall not

commit adultery’. But I say to you that every one who looks at a woman

lustfully has already committed adultery with her in his heart” (Mt

5:21-22,27-28). “Jesus himself is the living ‘fulfilment’ of the Law”

inasmuch as he fulfils its authentic meaning by the total gift of himself: “he

himself becomes a living and personal Law,” who invites people to follow him;

through the Spirit, he gives the grace to share his own life and love and

provides the strength to bear witness to that love in personal choices and

actions (cf. Jn 13:34-35).

“If

you wish to be perfect” (Mt 19:21)

16.

The answer he receives about the commandments does not satisfy the young man,

who asks Jesus a further question. “I have kept all these; ‘what do I still

lack?’“ (Mt 19:20). It is not easy to say with a clear conscience “I have

kept all these”, if one has any understanding of the real meaning of the

demands contained in God’s Law. And yet, even though he is able to make this

reply, even though he has followed the moral ideal seriously and generously from

childhood, the rich young man knows that he is still far from the goal: before

the person of Jesus he realizes that he is still lacking something. It is his

awareness of this insufficiency that Jesus addresses in his final answer.

Conscious of “the young man’s yearning for something greater, which would

transcend a legalistic interpretation of the commandments,” the Good Teacher

invites him to enter upon the path of perfection: “If you wish to be perfect,

go, sell your possessions and give the money to the poor, and you will have

treasure in heaven; then come, follow me” (Mt 19:21).

Like

the earlier part of Jesus’ answer, this part too must be read and interpreted

in the context of the whole moral message of the Gospel, and in particular in

the context of the Sermon on the Mount, the Beatitudes (cf. Mt 5:3-12), the

first of which is precisely the Beatitude of the poor, the “poor in spirit”

as Saint Matthew makes clear (Mt 5:3), the humble. In this sense it can be said

that the Beatitudes are also relevant to the answer given by Jesus to the young

man’s question: “What good must I do to have eternal life?”. Indeed, each

of the Beatitudes promises, from a particular viewpoint, that very “good”

which opens man up to eternal life, and indeed is eternal life.

“The

Beatitudes” are not specifically concerned with certain particular rules of

behaviour. Rather, they speak of basic attitudes and dispositions in life and

therefore they “do not coincide exactly with the commandments.” On the other

hand, “there is no separation or opposition” between the Beatitudes and the

commandments: both refer to the good, to eternal life. The Sermon on the Mount

begins with the proclamation of the Beatitudes, but also refers to the

commandments (cf. Mt 5:20-48). At the same time, the Sermon on the Mount

demonstrates the openness of the commandments and their orientation towards the

horizon of the perfection proper to the Beatitudes. These latter are above all

“promises,” from which there also indirectly flow “normative

indications” for the moral life. In their originality and profundity they are

a sort of “self-portrait of Christ,” and for this very reason are

“invitations to discipleship and to communion of life with Christ.”[26]

17.

We do not know how clearly the young man in the Gospel understood the profound

and challenging import of Jesus’ first reply: “If you wish to enter into

life, keep the commandments”. But it is certain that the young man’s

commitment to respect all the moral demands of the commandments represents the

absolutely essential ground in which the desire for perfection can take root and

mature, the desire, that is, for the meaning of the commandments to be

completely fulfilled in following Christ. Jesus’ conversation with the young

man helps us to grasp “the conditions for the moral growth of man, who has

been called to perfection:” the young man, having observed all the

commandments, shows that he is incapable of taking the next step by himself

alone. To do so requires mature human freedom (“If you wish to be perfect”)

and God’s gift of grace (“Come, follow me”).

“Perfection

demands that maturity in self-giving to which human freedom is called.” Jesus

points out to the young man that the commandments are the first and

indispensable condition for having eternal life; on the other hand, for the

young man to give up all he possesses and to follow the Lord is presented as an

invitation: “If you wish...”. These words of Jesus reveal the particular

dynamic of freedom’s growth towards maturity, and at the same time “they

bear witness to the fundamental relationship between freedom and divine law.”

Human freedom and God’s law are not in opposition; on the contrary, they

appeal one to the other. The follower of Christ knows that his vocation is to

freedom. “You were called to freedom, brethren” (Gal 5:13), proclaims the

Apostle Paul with joy and pride. But he immediately adds: “only do not use

your freedom as an opportunity for the flesh, but through love be servants of

one another” (ibid.). The firmness with which the Apostle opposes those who

believe that they are justified by the Law has nothing to do with man’s

“liberation” from precepts. On the contrary, the latter are at the service

of the practice of love: “For he who loves his neighbour has fulfilled the

Law. The commandments, ‘You shall not commit adultery; You shall not murder;

You shall not steal; You shall not covet,’ and any other commandment, are

summed up in this sentence, “You shall love your neighbour as yourself “

(Rom 13:8-9). Saint Augustine, after speaking of the observance of the

commandments as being a kind of incipient, imperfect freedom, goes on to say:

“Why, someone will ask, is it not yet perfect? Because ‘I see in my members

another law at war with the law of my reason’ ... In part freedom, in part

slavery: not yet complete freedom, not yet pure, not yet whole, because we are

not yet in eternity. In part we retain our weakness and in part we have attained

freedom. All our sins were destroyed in Baptism, but does it follow that no

weakness remained after iniquity was destroyed? Had none remained, we would live

without sin in this life. But who would dare to say this except someone who is

proud, someone unworthy of the mercy of our deliverer?... Therefore, since some

weakness has remained in us, I dare to say that to the extent to which we serve

God we are free, while to the extent that we follow the law of sin, we are still

slaves”.[27]

18.

Those who live “by the flesh” experience God’s law as a burden, and indeed

as a denial or at least a restriction of their own freedom. On the other hand,

those who are impelled by love and “walk by the Spirit” (Gal 5:16), and who

desire to serve others, find in God’s Law the fundamental and necessary way in

which to practise love as something freely chosen and freely lived out. Indeed,

they feel an interior urge--a genuine “necessity” and no longer a form of

coercion--not to stop at the minimum demands of the Law, but to live them in

their “fullness”. This is a still uncertain and fragile journey as long as

we are on earth, but it is one made possible by grace, which enables us to

possess the full freedom of the children of God (cf. Rom 8:21) and thus to live

our moral life in a way worthy of our sublime vocation as “sons in the Son”.

This

vocation to perfect love is not restricted to a small group of individuals.

“The invitation,” “go, sell your possessions and give the money to the

poor”, and the promise “you will have treasure in heaven”, “are meant

for everyone,” because they bring out the full meaning of the commandment of

love for neighbour, just as the invitation which follows, “Come, follow me”,

is the new, specific form of the commandment of love of God. Both the

commandments and Jesus’ invitation to the rich young man stand at the service

of a single and indivisible charity, which spontaneously tends towards that

perfection whose measure is God alone: “You, therefore, must be perfect, as

your heavenly Father is perfect” (Mt 5:48). In the Gospel of Luke, Jesus makes

even clearer the meaning of this perfection: “Be merciful, even as your Father

is merciful” (Lk 6:36).

“Come,

follow me” (Mt 19:2 1)

19.

The way and at the same time the content of this perfection consist in the

following of Jesus, “sequela Christi,” once one has given up one’s own

wealth and very self. This is precisely the conclusion of Jesus’ conversation

with the young man: “Come, follow me” (Mt 19:21). It is an invitation the

marvellous grandeur of which will be fully perceived by the disciples after

Christ’s Resurrection, when the Holy Spirit leads them to all truth (cf. Jn

16:13).

It

is Jesus himself who takes the initiative and calls people to follow him. His

call is addressed first to those to whom he entrusts a particular mission,

beginning with the Twelve; but it is also clear that every believer is called to

be a follower of Christ (cf. Acts 6:1). “Following Christ is thus the

essential and primordial foundation of Christian morality:” just as the people

of Israel followed God who led them through the desert towards the Promised Land

(cf. Ex 13:21), so every disciple must follow Jesus, towards whom he is drawn by

the Father himself (cf. Jn 6:44).

This

is not a matter only of disposing oneself to hear a teaching and obediently

accepting a commandment. More radically, it involves “holding fast to the very

person of Jesus,” partaking of his life and his destiny, sharing in his free

and loving obedience to the will of the Father. By responding in faith and

following the one who is Incarnate Wisdom, the disciple of Jesus truly becomes

“a disciple of God” (cf. Jn 6:45). Jesus is indeed the light of the world,

the light of life (cf. Jn 8:12). He is the shepherd who leads his sheep and

feeds them (cf. Jn 10:11-16); he is the way, and the truth, and the life (cf. Jn

14:6). It is Jesus who leads to the Father, so much so that to see him, the Son,

is to see the Father (cf. Jn 14:6-10). And thus to imitate the Son, “the image

of the invisible God” (Col 1:15), means to imitate the Father.

20.

“Jesus asks us to follow him and to imitate him along the path of love, a love

which gives itself completely to the brethren out of love for God:” “This is

my commandment, that you love one another as I have loved you” (Jn 15:12). The

word “as” requires imitation of Jesus and of his love, of which the washing

of feet is a sign: “If I then, your Lord and Teacher, have washed your feet,

you also ought to wash one another’s feet. For I have given you an example,

that you should do as I have done to you” (Jn 13:14-15). Jesus’ way of

acting and his words, his deeds and his precepts constitute the moral rule of

Christian life. Indeed, his actions, and in particular his Passion and Death on

the Cross, are the living revelation of his love for the Father and for others.

This is exactly the love that Jesus wishes to be imitated by all who follow him.

It is “the ‘new’ commandment:” “A new commandment I give to you, that

you love one another; even as I have loved you, that you also love one another.

By this all men will know that you are my disciples, if you have love for one

another” (Jn 13:34-35). The word “as” also indicates the “degree” of

Jesus’ love, and of the love with which his disciples are called to love one

another. After saying: “This is my commandment, that you love one another as I

have loved you” (Jn 15:12), Jesus continues with words which indicate the

sacrificial gift of his life on the Cross, as the witness to a love “to the

end” (Jn 13:1): “Greater love has no man than this, that a man lay down his

life for his friends” (Jn 15:13).

As

he calls the young man to follow him along the way of perfection, Jesus asks him

to be perfect in the command of love, in “his” commandment: to become part

of the unfolding of his complete giving, to imitate and rekindle the very love

of the “Good” Teacher, the one who loved “to the end”. This is what

Jesus asks of everyone who wishes to follow him: “If any man would come after

me, let him deny himself and take up his cross and follow me” (Mt 16:24).

21.

“Following Christ” is not an outward imitation, since it touches man at the

very depths of his being. Being a follower of Christ means “becoming conformed

to him” who became a servant even to giving himself on the Cross (cf. Phil

2:5-8). Christ dwells by faith in the heart of the believer (cf. Eph 3:17), and

thus the disciple is conformed to the Lord. This is the “effect of grace,”

of the active presence of the Holy Spirit in us.

Having

become one with Christ, the Christian “becomes a member of his Body, which is

the Church” (cf. 1 Cor 12:13,27). By the work of the Spirit, Baptism radically

configures the faithful to Christ in the Paschal Mystery of death and

resurrection; it “clothes him” in Christ (cf. Gal 3:27): “Let us rejoice

and give thanks”, exclaims Saint Augustine speaking to the baptized, “for we

have become not only Christians, but Christ (...). Marvel and rejoice: we have

become Christ!”.[28] Having died to sin, those who are baptized receive new

life (cf. Rom 6:3-11): alive for God in Christ Jesus, they are called to walk by

the Spirit and to manifest the Spirit’s fruits in their lives (cf. Gal

5:16-25). Sharing in the “Eucharist,” the sacrament of the New Covenant (cf.

1 Cor 11:23-29), is the culmination of our assimilation to Christ, the source of

“eternal life” (cf. Jn 6:51-58), the source and power of that complete gift

of self, which Jesus--according to the testimony handed on by Paul--commands us

to commemorate in liturgy and in life: “As often as you eat this bread and

drink the cup, you proclaim the Lord’s death until he comes” (1 Cor 11:26).

“With

God all things are possible” (Mt 19:26)

22.

The conclusion of Jesus’ conversation with the rich young man is very

poignant: “When the young man heard this, he went away sorrowful, for he had

many possessions” (Mt 19:22). Not only the rich man but the disciples

themselves are taken aback by Jesus’ call to discipleship, the demands of

which transcend human aspirations and abilities: “When the disciples heard

this, they were greatly astounded and said, ‘Then who can be saved?”‘ (Mt

19:25). “But the Master refers them to God’s power:” “With men this is

impossible, but with God all things are possible” (Mt 19:26).

In

the same chapter of Matthew’s Gospel (19:3-10), Jesus, interpreting the Mosaic

Law on marriage, rejects the right to divorce, appealing to a “beginning”

more fundamental and more authoritative than the Law of Moses: God’s original

plan for mankind, a plan which man after sin has no longer been able to live up

to: “For your hardness of heart Moses allowed you to divorce your wives, but

from the beginning it was not so” (Mt 19:8). Jesus’ appeal to the

“beginning” dismays the disciples, who remark: “If such is the case of a

man with his wife, it is not expedient to marry” (Mt 19:10). And Jesus,

referring specifically to the charism of celibacy “for the Kingdom of

Heaven” (Mt 19:12), but stating a general rule, indicates the new and

surprising possibility opened up to man by God’s grace. “He said to them:

‘Not everyone can accept this saying, but only those to whom it is given”‘

(Mt 19:11).

To

imitate and live out the love of Christ is not possible for man by his own

strength alone. He becomes “capable of this love only by virtue of a gift

received.” As the Lord Jesus receives the love of his Father, so he in turn

freely communicates that love to his disciples: “As the Father has loved me,

so have I loved you; abide in my love” (Jn 15:9). “Christ’s gift is his

Spirit,” whose first “fruit” (cf. Gal 5:22) is charity: “God’s love

has been poured into our hearts through the Holy Spirit which has been given to

us” (Rom 5:5). Saint Augustine asks: “Does love bring about the keeping of

the commandments, or does the keeping of the commandments bring about love?”

And he answers: “But who can doubt that love comes first? For the one who does

not love has no reason for keeping the commandments”.[29]

23.

“The law of the Spirit of life in Christ Jesus has set me free from the law of

sin and death” (Rom 8:2). With these words the Apostle Paul invites us to

consider in the perspective of the history of salvation, which reaches its

fulfilment in Christ, “the relationship between the (Old) Law and grace (the

New Law).” He recognizes the pedagogic function of the Law, which, by enabling

sinful man to take stock of his own powerlessness and by stripping him of the

presumption of his self-sufficiency, leads him to ask for and to receive “life

in the Spirit”. Only in this new life is it possible to carry out God’s

commandments. Indeed, it is through faith in Christ that we have been made

righteous (cf. Rom 3:28): the “righteousness” which the Law demands, but is

unable to give, is found by every believer to be revealed and granted by the

Lord Jesus. Once again it is Saint Augustine who admirably sums up this Pauline

dialectic of law and grace: “The law was given that grace might be sought; and

grace was given, that the law might be fulfilled”.[30]

Love

and life according to the Gospel cannot be thought of first and foremost as a

kind of precept, because what they demand is beyond man’s abilities. They are

possible only as the result of a gift of God who heals, restores and transforms

the human heart by his grace: “For the law was given through Moses; grace and

truth came through Jesus Christ” (Jn 1:17). The promise of eternal life is

thus linked to the gift of grace, and the gift of the Spirit which we have

received is even now the “guarantee of our inheritance” (Eph 1:14).

24.

And so we find revealed the authentic and original aspect of the commandment of

love and of the perfection to which it is ordered: we are speaking of a

“possibility opened up to man exclusively by grace,” by the gift of God, by

his love. On the other hand, precisely the awareness of having received the

gift, of possessing in Jesus Christ the love of God, generates and sustains

“the free response” of a full love for God and the brethren, as the Apostle

John insistently reminds us in his first Letter: “Beloved, let us love one

another; for love is of God and knows God. He who does not love does not know

God; for God is love... Beloved, if God so loved us, we ought also to love one

another.. . We love, because he first loved us” (1 Jn 4:7-8,11,19).

This

inseparable connection between the Lord’s grace and human freedom, between

gift and task, has been expressed in simple yet profound words by Saint

Augustine in his prayer: “Da quod iubes et iube quod vis” (grant what you

command and command what you will).[31]

“The gift does not lessen but reinforces the moral demands of love:” “This is his commandment, that we should believe in the name of his Son Jesus Christ and love one another just as he has commanded us” (1 Jn 3:32). One can “abide” in love only by keeping the commandments, as Jesus states: “If you keep my commandments, you will abide in my love, just as I have kept my Father’s commandments and abide in his love” (Jn 15:10).

|

CONSCIENCE FORMED BY: [1] EXPERIENCE [2] ORTHODOX TEACHING [3] The HOLY SPIRIT and PRAYER |

|

CONSCIENCE LOOKS OUT & INTERPRETS MEANING (GLORY) of GOD in A CREATION that REFLECTS GOD'S WILL: |

|

|

THIS IS NATURAL CONTEMPLATION

|

[»Light] [»Heart] [» Unity Faith & Morals]

Going to the heart of the moral message of Jesus and the preaching of the Apostles, and summing up in a remarkable way the great tradition of the Fathers of the East and West, and of Saint Augustine in particular,[32] Saint Thomas was able to write that “the New Law is the grace of the Holy Spirit given through faith in Christ.”[33] The external precepts also mentioned in the Gospel dispose one for this grace or produce its effects in one’s life. Indeed, the New Law is not content to say what must be done, but also gives the power to “do what is true” (cf. Jn 3:21). Saint John Chrysostom likewise observed that the New Law was promulgated at the descent of the Holy Spirit from heaven on the day of Pentecost, and that the Apostles “did not come down from the mountain carrying, like Moses, tablets of stone in their hands; but they came down carrying the Holy Spirit in their hearts... having become by his grace a living law, a living book”.[34]

[»Light] [»Heart] [» Unity Faith & Morals]

“Lo, I am with you always, to the close of the age” (Mt 28:20)

25.

Jesus’ conversation with the rich young man continues, in a sense, “in every

period of history, including our own.” The question: “Teacher, what good

must I do to have eternal life?” arises in the heart of every individual, and

it is Christ alone who is capable of giving the full and definitive answer. The

Teacher who expounds God’s commandments, who invites others to follow him and

gives the grace for a new life, is always present and at work in our midst, as

he himself promised: “Lo, I am with you always, to the close of the age” (Mt

28:20). “Christ’s relevance for people of all times is shown forth in his

body, which is the Church.” For this reason the Lord promised his disciples

the Holy Spirit, who would “bring to their remembrance” and teach them to

understand his commandments (cf. Jn 14:26), and who would be the principle and

constant source of a new life in the world (cf. Jn 3:5-8; Rom 8:1-13).

The

moral prescriptions which God imparted in the Old Covenant, and which attained

their perfection in the New and Eternal Covenant in the very person of the Son

of God made man, must be “faithfully kept and continually put into practice”

in the various different cultures throughout the course of history. The task of

interpreting these prescriptions was entrusted by Jesus to the Apostles and to

their successors, with the special assistance of the Spirit of truth: “He who

hears you hears me” (Lk 10:16). By the light and the strength of this Spirit

the Apostles carried out their mission of preaching the Gospel and of pointing

out the “way” of the Lord (cf. Acts 18:25), teaching above all how to follow

and imitate Christ: “For to me to live is Christ” (Phil 1:21).

|

UNITY of FAITH & MORALITY DEFINITIVE of CHRISTIANS SINCE the EARLY CHURCH: e.g. Moral exhortations of Didache, Barnabas, Hermas, Clement |

|

26. In the “moral catechesis of the Apostles,” besides exhortations and directions connected to specific historical and cultural situations, we find an ethical teaching with precise rules of behaviour. This is seen in their Letters, which contain the interpretation, made under the guidance of the Holy Spirit, of the Lord’s precepts as they are to be lived in different cultural circumstances (cf. Rom 12-15; 1 Cor 11-14; Gal 5-6; Eph 4-6; Col 3-4; 1 Pt and Jas). From the Church’s beginnings, the Apostles, by virtue of their pastoral responsibility to preach the Gospel, “were vigilant over the right conduct of Christians,”[35] just as they were vigilant for the purity of the faith and the handing down of the divine gifts in the sacraments.[36] The first Christians, coming both from the Jewish people and from the Gentiles, differed from the pagans not only in their faith and their liturgy but also in the witness of their moral conduct, which was inspired by the New Law.[37] The Church is in fact a communion both of faith and of life; her rule of life is “faith working through love” (Gal 5:6).

No damage must be done to the “harmony between faith and life: the unity of the Church” is damaged not only by Christians who reject or distort the truths of faith but also by those who disregard the moral obligations to which they are called by the Gospel (cf. 1 Cor 5:9-13). The Apostles decisively rejected any separation between the commitment of the heart and the actions which express or prove it (cf. 1 Jn 2:3-6). And ever since Apostolic times the Church’s Pastors have unambiguously condemned the behaviour of those who fostered division by their teaching or by their actions.[38]

[»Light] [»Heart] [» Unity Faith & Morals]

27.

Within the unity of the Church, promoting and preserving the faith and the moral

life is the task entrusted by Jesus to the Apostles (cf. Mt 28:19-20), a task

which continues in the ministry of their successors. This is apparent from the

“living Tradition,” whereby--as the Second Vatican Council teaches--”the

Church, in her teaching, life and worship, perpetuates and hands on to every

generation all that she is and all that she believes. This Tradition which comes

from the Apostles, progresses in the Church under the assistance of the Holy

Spirit”.[39] In the Holy Spirit, the Church receives and hands down the

Scripture as the witness to the “great things” which God has done in history

(cf. Lk 1:49); she professes by the lips of her Fathers and Doctors the truth of

the Word made flesh, puts his precepts and love into practice in the lives of

her Saints and in the sacrifice of her Martyrs, and celebrates her hope in him

in the Liturgy. By this same Tradition Christians receive “the living voice of

the Gospel”,[40] as the faithful expression of God’s wisdom and will.

Within

Tradition, “the authentic interpretation” of the Lord’s law develops, with

the help of the Holy Spirit. The same Spirit who is at the origin of the

Revelation of Jesus’ commandments and teachings guarantees that they will be

reverently preserved, faithfully expounded and correctly applied in different

times and places. This constant “putting into practice” of the commandments

is the sign and fruit of a deeper insight into Revelation and of an

understanding in the light of faith of new historical and cultural situations.

Nevertheless, it can only confirm the permanent validity of revelation and

follow in the line of the interpretation given to it by the great Tradition of

the Church’s teaching and life, as witnessed by the teaching of the Fathers,

the lives of the Saints, the Church’s Liturgy and the teaching of the

Magisterium.

In

particular, as the Council affirms, “the task of authentically interpreting

the word of God, whether in its written form or in that of Tradition, has been

entrusted only to those charged with the Church’s living Magisterium, whose

authority is exercised in the name of Jesus Christ”.[41] The Church, in her

life and teaching, is thus revealed as “the pillar and bulwark of the truth”

(1 Tm 3:15), including the truth regarding moral action. Indeed, “the Church

has the right always and everywhere to proclaim moral principles, even in

respect of the social order, and to make judgments about any human matter in so

far as this is required by fundamental human rights or the salvation of

souls.”[42]

Precisely

on the questions frequently debated in moral theology today and with regard to

which new tendencies and theories have developed, the Magisterium, in fidelity

to Jesus Christ and in continuity with the Church’s tradition, senses more

urgently the duty to offer its own discernment and teaching, in order to help

man in his journey towards truth and freedom.

ENDNOTES

1. Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World “Gaudium et Spes,”

22.

2.

Cf. SECOND VATICAN ECUMENICAL COUNCIL, Dogmatic Constitution on the Church

“Lumen Gentium,” 1.

3.

Cf. ibid., 9.

4.

SECOND VATICAN ECUMENICAL COUNCIL, Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the

Modern World “Gaudium et Spes,” 4.

5.

PAUL VI, “Address” to the General Assembly of the United Nations (4 October

1965), 1: AAS 57 (1965), 878; cf. Encyclical Letter “Populorum Progressio”

(26 March 1967), 13: AAS 59 (1967), 263-264.

6.

Cf. SECOND VATICAN ECUMENICAL COUNCIL, Pastoral Constitution on the Church in

the Modern World “Gaudium et Spes,” 16.

7.

Dogmatic Constitution on the Church Lumen Gentium, 16.

8.

Pius XII had already pointed out this doctrinal development: cf. “Radio

Message” for the Fiftieth Anniversary of the Encyclical Letter “Rerum

Novarum” of Leo XIII (1 June 1941): AAS 33 (1941), 195-205. Also JOHN XXIII,

Encyclical Letter “Mater et Magistra” (15 May 1961): AAS 53 (1961), 410-413.

9.

Apostolic Letter “Spiritus Domini” (1 August 1987): AAS 79(1987), 1374.

10.

“Catechism of the Catholic Church,” No. 1692.

11.

Apostolic Constitution “Fidei Depositum” (11 October 1992), 4.

12.

Cf. SECOND VATICAN ECUMENICAL COUNCIL, Dogmatic Constitution on Divine

Revelation “Dei Verbum,” 10.

13.

Cf. Apostolic Epistle “Parati semper” to the Young People of the World on

the occasion of the International Year of Youth (31 March 1985), 2-8: AAS 77

(1985), 581-600.

14.

Cf. Decree on Priestly Formation “Optatam Totius,” 16.

15.

Encyclical Letter “Redemptor Hominis” (4 March 1979), 13: AAS 71 (1979),

282.

16.

Ibid 10; loc. cit., 274.

17.

“Exameron,” Dies VI, Sermo IX, 8, 50: CSEL 32, 241.

18.

SAINT LEO THE GREAT, “Sermo XCII,” Chap. III PL 54 454.

19.

SAINT THOMAS AQUINAS, “In Duo Praecepta Caritatis et in Decem Legis Praecepta.

Prologus: Opuscula Theologica,” II, NO. 1129, Ed. Taurinen. (1954), 245; cf.

“Summa Theologiae,” I-II, q. 91, a. 2; “Catechism of the Catholic

Church,” NO. 1955.

20.

Cf. SAINT MAXIMUS THE CONFESSOR, “Quaestiones ad Thalassium,” Q. 64: PG 90,

723-728.

21.

SECOND VATICAN ECUMENICAL COUNCIL, Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the

Modern World “Gaudium et Spes,” 24.

22.

“Catechism of the Catholic Church,” NO. 2070.

23.

“In Johannis Evangelium Tractatus,” 41, 10: CCL 36, 363.

24.

Cf. SAINT AUGUSTINE, “De Sermone Domini in Monte,” I, 1, 1: CCL 35, 1-2.

25.

“In Psalmum CXVIII Expositio”, Sermo 18 37 PL 15, 1541; cf. SAINT CHROMATIUS

OF AQUILEIA, “Tractatus in Matthaeum,” XX, I, 1-4: CCL 9/A, 291-292.

26.

Cf. “Catechism of the Catholic Church,” NO. 1717.

27.

“In Johannis Evangelium Tractatus,” 41, 10: CCL 36, 363.

28.

Ibid, 21, 8 CCL 36 216.

29.

Ibid., 82, 3: CCL 36, 533.

30.

“De Spiritu et Littera,” 19, 34: CSEL 60 187.

31.

“Confessiones,” X, 29 40 CCL 27, 176; cf “De Gratia el Libero

Arbitrio,” XV: PL 44 899.

32.

Cf. “De Spiritu et Littera,” 21, 36; 26, 46: CSEL 60, 189-190 200-201 .

33.

Cf. “Summa Theologiae,” I-II, q. 106, a. 1 conclusion and ad 2um.

34.

“In Matthaeum,” Hom. I, 1: PG 57, 15.

35.

Cf. SAINT IRENAEUS, “Adversus Haereses,” IV, 26, 2-5: SCh 100/2, 718-729.

36.

Cf. SAINT JUSTIN, “Apologia,” I, 66: PG 6, 427-430.

37.

Cf. I Pt 2: 12 ff.; Cf. “Didache,” II, 2: “Patres Apostolici;” ed. F. X.

Funk, I, 6-9; CLEMENT OF ALEXANDRIA, “Paelagogus,” I, 10; II, 10: PG 8,

355-364; 497-536; TERTULLIAN, “Apologeticum,” IX, 8: CSEL, 69, 24.

38.

Cf. SAINT IGNATIUS OF ANTIOCH, “Ad Magnesios,” VI, 1-2: “Patres

Apostolici,” ed. F. X. Funk, I, 234-235; SAINT IRENAEUS, “Adversus

Haereses,” IV, 33: 1, 6, 7: SCh 100/2, 802-805; 814-815; 816-819.

39.

Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation “Dei Verbum,” 8.

40.

Cf. ibid.

41.

Ibid, 10.

42.

“Code of Canon Law,” Canon 747, 2.

xcxxcxxc F