|

|

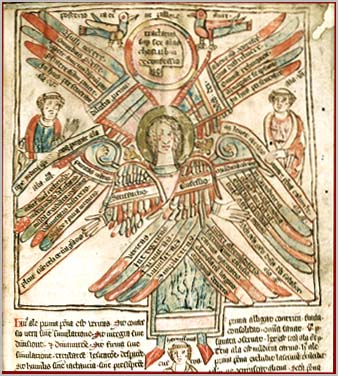

SIX-WINGED SERAPHIM in ACHARD of ST. VICTOR

[THE FIVE FEATHERS of the SIX WINGS]

|

|

PL images: 176 1007-1010

|

|

At the same time that the excerpt from Hugh’s De arca Noe morali was appearing in manuscripts containing the cherub figure, a second text was also in circulation with the image. Unlike the first text, which makes no reference to the categories on the angel’s wings, this one directly addresses the content of the diagram.18 Marie Thérèse d’Alverny believes this tract to be the work of Alan of Lille.19

The text launches without fanfare into an orderly explication of the diagram’s elements.20

ONE-CONFESSION

[1.1] The first wing, confession of sin, is defined as the lament for one’s infirmity, ignorance, and malice.

[1.2] The author places emphasis on the second feather: integrity. He cautions against spreading confession among different priests, a hypocrisy that can impede the winning of mercy. He also encourages his reader to tell all the details of his sin in confession and to think of how his repeated sins aggravate God. He should leave no sin unrecalled because such negligence or concealment could be the cause of damnation.

[1.3] The third feather, firmness in confession, also receives much attention. As in feather two, memory is significant. Alan writes, “Let the studious scrutinizing and recall into memory of motives and works light up the shadows of forgetfulness. Let the fervor of spirit unveil and destroy the torpor and tepidness of negligence. Let absolutely no negligence overlook necessity.”21 One must work for one’s own self improvement through examining clearly and thoroughly not only the course of one’s actions but one’s motives for acting.

TWO-SATISFACTION

The second wing is making amends after confession. This cures the illness uncovered by preparatory compunction and recall of sin before the priest. Making amends is the explicit execution of the enjoined penance or a cutting short and correcting of sin which should be done with fear but also with the hope of forgiveness. The measure of correction depends on the quality and quantity of the fault. Punishment must fit the crime but it is better to pay a higher price in penance than to be lax in making satisfaction. As in confession, integrity is a key factor: one must be sincere in the performance of one’s penance in order to attain true forgiveness.

[2.1] The first feather of the second wing represents the renunciation of sins, particularly those generated by vanity, iniquity, malignancy, and impiety. Vanity reflects on the self; iniquity is done against a neighbor; malign behavior is an offense against a brother; impiety is a crime against God. Each of feathers two to five corresponds to a specific type of person manifesting each type of vice. [2.2] Thus, effusive tears (the second feather) should be shed by the self-centered. [2.3] Feather three, wearing down the flesh, is enjoined to a misanthrope. [2.4] Feather four, largess of charitable giving, is aimed at a greedy man who exploits his brothers. [2.5] Feather five, devotion in prayer, seeks to correct the impious.

THREE – BODILY PURITY

The third wing is purity of the flesh, the conqueror of the vice that eradicates all the virtues: self-indulgence.

[3.1] The first feather is modesty in seeing, that is, avoiding women and their charms. [3.2] The second feather is chastity of hearing, not listening to lies, criticism, blasphemy, curses, provocations, obscenities, false accusations, immodest songs, or theatrical performances. [3.3] The third is modesty of smell because, though a man may be seemly on the outside, he may be rotten on the inside. [3.4] The fourth feather is temperance in taste or moderation in eating and drinking. [3.5] The fifth is sanctified touch, one’s bodily actions remaining in the service of God’s commands.

FOUR – PURITY of MIND

The fourth wing, purity of mind, is one of the most important to Alan. It is the path to contemplation, containing the items necessary for true meditation on the divine. Alan places emphasis on inner disposition rather than on outward action in his explication of this wing.

[4.1] The first feather is genuine emotion. Here the person’s desires should be correct and sincere. The devotee is encouraged to desire what he ought to desire and to be sincere when he loves in the way ordained by God and reason. [4.2] The second feather is delight in God. This enables the individual to feel joy in contemplation. [4.3] The third is chaste and ordered thought at all times. [4.4] The fourth is sanctity of will. Willing correctly enables the person to achieve personal peace, which is the foundation of the Christian religion. Alan asserts that angels hasten to help those who purify themselves by means of good will. Though such men sometimes err, their purity shines through and they are excused for their actions. [4.5] The final feather on the fourth wing is simple and pure intention. As in so many other instances in Alan’s explication of the cherub figure, action is less important here than disposition. Just like a moneychanger one must weigh one’s motives to be sure they are correct.

FIVE – LOVE of NEIGHBOR; SIX – LOVE of GOD

The fifth and sixth wing, love of neighbor and love of God, hardly receive any explication, as if their categories were self-evident. However, Alan’s commentary makes clear that they are the crowning achievements of the religious life.

The sixth wing, love of God, is particularly significant because it represents the state in the individual’s religious life where he attains the heights of mystical ascent. He leaves behind his own property, will, and self, giving himself completely to the will of God.

Like the excerpt from Hugh, Alan’s text provides a means for the viewer of the cherub image to ascend in stages to the celestial vision. Yet, whereas Hugh suggests that moral improvement and mystical ascent are begun in study and culminated in action, Alan stresses confession, penance, and virtuous action as the foundation of contemplation. For Alan, it is only in the pursuit of an ethical life that the individual’s consciousness can be purified enough to climb to the heights of contemplation of the divine.

|

|

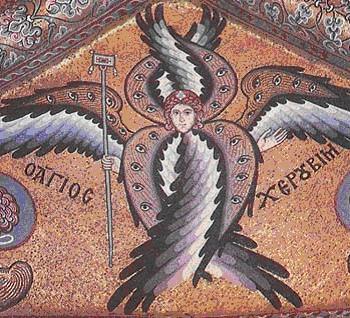

SIX-WINGED SERAPHIM in HUGH of ST. VICTOR

Medieval Representation of the Cherub and the Diagram in Beinecke MS 416 By: Brian Noell

[The Cherub (sic “Seraph”) in Hugh of St. Victor]

The cherub with six inscribed wings was linked from early in its existence to the teachings of the twelfth-century educator Hugh of St. Victor, particularly his explication of the meaning of Isaiah 6 in De arca Noe morali. Edited by an English Augustinian named Clement, 14 Hugh’s discussion of the seraphim appears as early as the latter twelfth-century in a manuscript from the Cistercian monastery of Sawley.15 In this excerpt Hugh asserts that the seraphim represent the two testaments of the scriptures. He asserts that it is possible for man to climb past the chorus of angels and reach the divine presence through the knowledge of them. However, this is only to be done through submitting the seraphim (scriptures) to threefold exegesis. The three pairs of wings represent the three modes of explication:

[1] history,

[2] allegory,

[3] and tropology.

They are in pairs because they lead the spirits of readers to the love of both God and neighbor.

[1] The seraphim cover their bodies with one set of wings. This pair represents historical exegesis, the words and description that introduce the intellect to the actual events of the Bible. It is notable that Hugh departs from the biblical text in describing the disposition of this first pair of wings. Isaiah specifies that the seraphim cover their own faces with one pair of wings and makes no mention of the veiling of their bodies. Hugh conflates Isaiah’s vision with that of Ezekiel, with the result that the seraphim veil their own bodies with one pair of wings. This is similar to visual depictions of Isaiah’s vision in which the seraphim cover their bodies like Ezekiel’s angels and may even suggest that when Hugh was developing his discussion he had such images and not texts in mind.16

[2] The seraphim use one of the wings in their second set to veil God’s head while they cover God’s feet with the other. This disposition represents the allegorical understanding of scripture, by which the mind explores God’s body. In allegorical exegesis the student searches for the ways in which Old Testament history foretells the incarnation of Christ and the formation of the Church. Yet, the covering of the head and feet represent the fact that, in this mode of exegesis, the nature of God’s divinity is not revealed. Neither a beginning nor an end of God can be found. Interestingly, however, Hugh insists that, although the Bible states that the face of God is veiled, he wishes to depict it exposed. Grover Zinn believes that this places the viewer in the position of angel, rising in sanctity to behold the divine vision. Such a state is beyond that of Isaiah’s earthly vision of the Lord enthroned in which the face was veiled.17

[3] The student of the diagram ascends to the vision of the divine with the third pair of seraphic wings. This final set represents tropological exegesis, which the individual uses to exhort others to the study of good conduct. Having engaged in long study of the previous modes and having achieved moral understanding, the spiritual aspirant is finally encouraged to instruct others in what he has learned. He broadcasts what he perceives to be the ethical import of biblical events, yet he does so praising God and not himself. This text, passed down with a number of examples of the image of the cherub with six inscribed wings, stresses both the contemplative and the active elements in devotion. Not only should the student attend to the historical content and allegorical meaning of the Bible, he should also seek to garner moral lessons and to share them with his fellows. It is only in this last phase that the devotee can soar towards the beatific vision that Hugh optimistically believes to be attainable by mortal men.

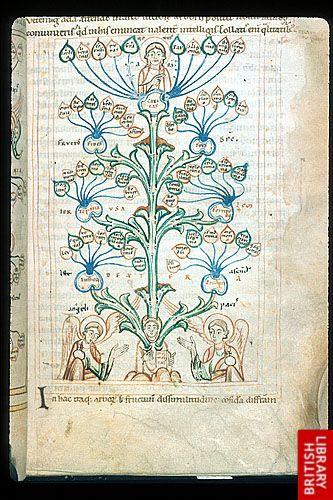

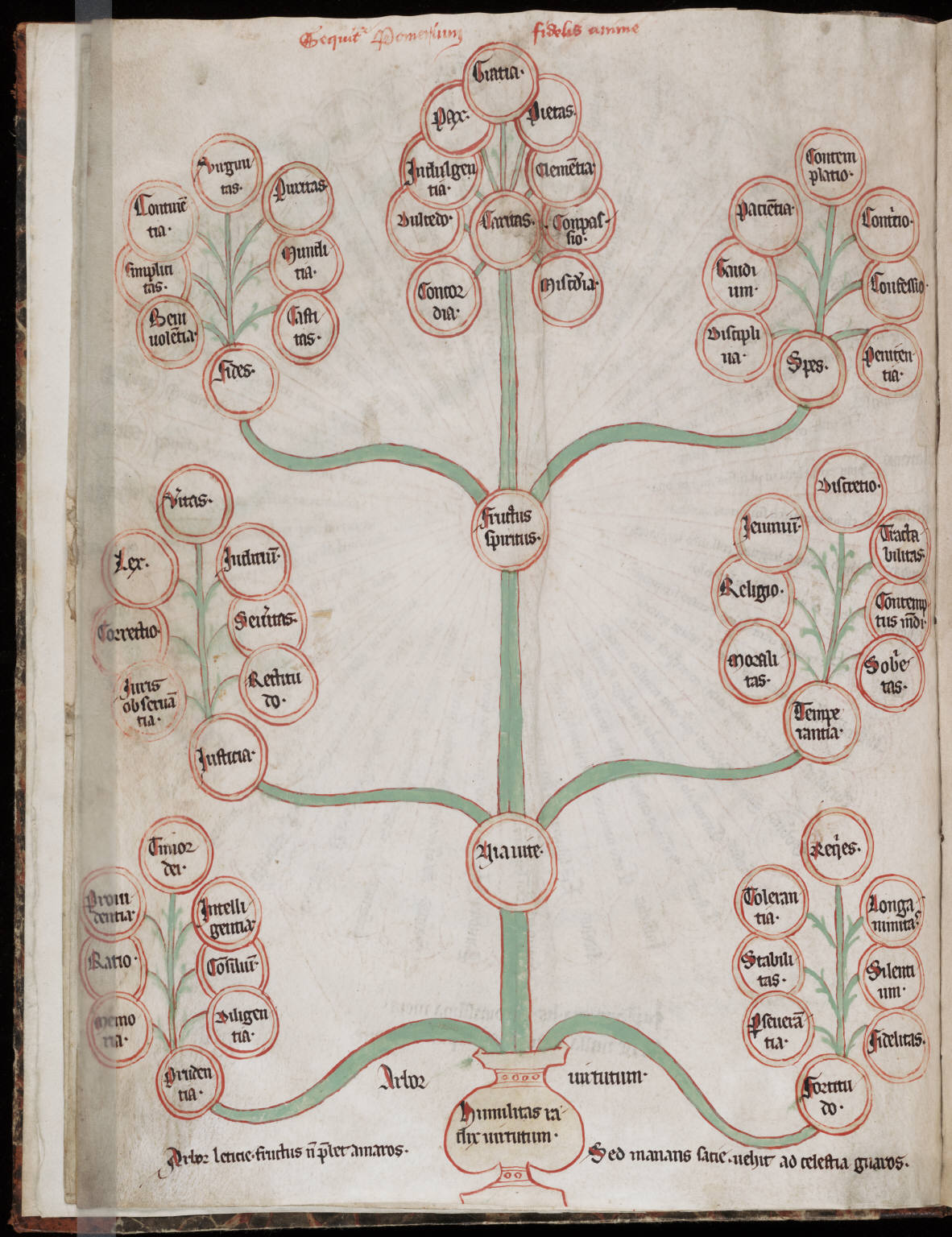

TREE of VIRTUES/LIFE and MYSTICAL PARADISE

PL images: 176 1007-1010

|

|

PL images: 176 1007-1010

|

|

PL images: 176 1007-1010

|

|

PL images: 176 1007-1010

survived from the period, place, and culture of the text:

This Webpage was created for a workshop held at Saint Andrew's Abbey, Valyermo, California in 1990