|

|

Abbot Blosius of Liessies |

|

|

Abbot Blosius of Liessies |

LOUIS de BLOIS, OSB (October 1506 - January 7, 1566), Flemish mystical writer, generally known under the name of Blosius, was born at the château of Donstienne, near Liège, of an illustrious family to which several crowned heads were allied.

He was educated at the court of the Netherlands with the future emperor Charles V of Germany, who remained to the last his staunch friend. At the age of fourteen he received the Benedictine habit in the monastery of Liessies in Hainaut, of which he became abbot in 1530. Charles V pressed in vain upon him the archbishopric of Cambrai, but Blosius studiously exerted himself in the reform of his monastery and in the composition of devotional works. He died at his monastery on the 7th of January 1566.

Blosius's works, which were written in Latin, have been translated into almost every European language, and have appealed not only to Roman Catholics, but to many English laymen of note, such as WE Gladstone and Lord Coleridge.

The best editions of his collected works are the first edition by J Frojus (Louvain, 1568), and the Cologne reprints (1572, 1587). His best-known works are:

the Institutio Spiritualis (Eng. trans., A Book of Spiritual Instruction, London, 1900)

Consolatio Pusillanimium (Eng. trans., Comfort for the Faint Hearted, London, 1903)

Sacellum Animae Fidelis (Eng. trans., The Sanctuary of the Faithful Soul, London, 1905)

All these three works were translated and edited by Father Bertrand Wilberforce, O.P., and have been reprinted several times; and especially Speculum Monachorum (French trans. by Félicité de Lamennais, Paris, 1809; Eng. trans., Paris, 1676; re-edited by Lord Coleridge, London, 1871, 1872, and inserted in Paternoster series, 1901).

1. Canon Vitae Spiritualis

2. Conclave animae fidelis: quo

continentur ista,

2.a. Speculum Spirituale

2.b. Monile Spirituale

2.c. Corona Spirituale

2.d. Scriniolum Spirituale

3. Cimeliarchion piarum precularum

4. Enchiridion parvulorum, Libri duo

5. Psychagogia, hoc est anime recreatio, quatuor libris distincta.

6. Collyrium hareticorum

7. Comparatio Regis et Monachi, libellus ex Graco D.Chrysostomi Latine conversus.

8. Consolatio Pusillanissium

9. Institutio spiritualis non parumn utilis iis qui ad vitae perfectioum contendunt: itemque exercitium piarum preccationum.

10. Brevis Regula Tyronis spiritualis

11. Margaritum spirituale, etc.

12. Sacellum animae fidelis

13. Facula illuminandis [et] ab errore avocandis haereticis accommoda

14. Speculum Monachorum Dacryano hactenus inscriptum.

See Georges de Blois, Louis de Blois, un Bénédictin au XVIe siècle (Paris, 1875), Eng. trans. by Lady Lovat (London, 1878, etc.).

This entry was originally from the 1911 Encyclopedia Britannica.

BIOGRAPHY

(by Roger. Hudleston)

From the Introduction to: A Mirror for Monks (Speculum Monachorum) Abbot Ludovicus Blosius, O.S.B Anon. tr. (Paris, 1676) rev. & ed. Roger Hudleston, O.S.B. (Downside Abbey, 1926); f

LUIS DE BLOIS, one of the ten children of Adrian de Blois, Sieur of Jumigny, and Catharine, nee Barbanson, his wife, was born at Donstienne, near Liege, province of Hainault, Flanders, in October, 1506.

While still a child he entered the household of the Archduke Charles—afterwards the Emperor Charles V—as one of his pages; but left it, when only fourteen years old, to enter the Benedictine Abbey of Liessies, in Hainault, where he received the monastic habit on October 25, 1520, and made his profession a year later.

The Abbot of Liessies at this date was Gilles Gippus, an elderly man of high moral character, but the standard of discipline in the Abbey was low; for, like many another monastic house at that period, Liessies had gradually declined into a relaxed observance of the holy Rule. The community, however, was not without members who longed to restore a stricter way of life, and one of these was the Novice-Master, Dom Jean Meurisse. This good monk soon realised that, in Louis de Blois, he had a novice of exceptional character, and to his careful training Blosius owed the firm grasp of monastic principle which enabled him, in later life, to achieve the “ Reform “ that made Liessies a model amongst the monasteries of the sixteenth century.

His noviciate over and his vows taken, Blosius was sent to study at the University of Louvain, returning doubtless to his monastery during the long summer vacations. In 1527 Abbot Gilles—who was now more than seventy years old and in failing health—being anxious lest, in the event of his death, some less worthy member of the community might be chosen to succeed him, took the unusual course of proposing to his monks that Blosius should be elected as his Coadjutor with right of succession.

The proposal must have seemed a startling one to the monks of Liessies, for the Abbot’s nominee was only twenty-one years old, and not yet ordained priest : and their acceptance of the scheme is the best testimony to the reputation that Blosius had already acquired among his brethren. The election took place while Blosius himself was absent at Louvain, the first news he had of it being the formal document announcing to him his election as Abbot-Coadjutor ! The appointment was confirmed by a Bull of Pope Paul III, and, on the death of Abbot Gilles in 1530, Blosius returned from Louvain to succeed him as thirty-fourth Abbot of Liessies, being ordained priest and blessed as Abbot in November of the same year.

From the first Blosius realised that the great work of his life would be to reform the observance in his monastery, but he knew that the task was one of great difficulty, requiring the utmost gentleness and tact. The monks of Liessies had lived all their monastic life under easy, relaxed conditions. Blosius himself was one of the youngest in the community, and any attempt to enforce a stricter way of living might arouse opposition, and possibly cause a schism in the monastery.

No doubt also Blosius knew—what all canonists admit—that a mitigation of the observance in a monastery may come about quite lawfully; e.g., by permission of the Holy See: by decree of the Superiors of the Order itself, so far as they are empowered to modify the Rule and its observance : and even by prescription or custom lawfully established, so long as such relaxations do not affect or alter in their nature the vows taken by the religious. On the other hand, the abolition of abuses in respect of obligations to which religious are bound by vow, is not “ reform “ in the proper sense of the word at all, since such obligations cannot be modifled by custom or prescription, but are always binding in conscience.

It seems clear, however, from the way in which Blosius went to work, that the monks of Liessies were not guilty of anything amounting to definite breach of vows, for his biographers tell us that, during the early years of his reign as Abbot, he bore the defects of his subjects with tolerance, rather than risk any internal conflict, or grave disturbance in the minds of his brethren: a thing he could not have done had the observance been so relaxed as to involve serious or general breach of vows.

In some countries—in France, for example —the custom of nominating courtiers, princes, or prelates as Abbots of monasteries in commendam, who merely absorbed the revenues of the houses which they left to go to ruin, had brought monastic life to the lowest ebb, and the monks themselves into contempt. In the Low Countries, however, as in England, this system was almost unknown, so the relaxed observance at Liessies cannot have been due to such a cause.

It would seem rather to have come about gradually as the result of prolonged civil disturbance, coupled with the intellectual upheaval and steady increase of luxury, among ecclesiastics and laymen alike, which characterised the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. Vocations were getting scarcer, and a custom had grown up of sending monks out to the priories and cells belonging to the greater abbeys, where, left to themselves, perhaps for many years, in circumstances which made conventual life impossible, the monks inevitably came to adopt a way of living differing little from that of laymen in the world. The influence of such members was bound to tell upon the community at large. “ What is the use,” they might ask, “ of training up our novices to strict discipline, when, after a few years in the monastery, they will be transplanted into conditions which make it impossible for them to continue such a mode of life

Blosius seems to have realised at once that the only way to remedy such a state of things was to build up in his monks, gradually and slowly, a sound monastic spirit, to which such ideas would be essentially repugnant. “ For eight years,” as the Bollandists put it in their Life, “ he had recourse to the divine goodness and opened his heart to God, imploring him to melt the dispositions of those who would not listen to his just remonstrances.” Then an event occurred which, at first sight, looked as if it would ruin all his hopes, but which, through God’s providence, produced in the end a directly opposite result.

In 1537, Francis I of France had invaded Flanders, then governed by Mary of Austria, Queen of Hungary, as Regent of her brother, the Emperor Charles V. Several small towns along the frontier were captured by the French troops, and it seemed not unlikely that Liessies also might fall into their hands.* The prospect filled Blosius with alarm. Should he and his monks remain and face the risk of capture; and if they did so, what would be the effect upon his work of reform ? The danger was considerable, and his predecessor, Abbot Gippus —who had been called upon to face the same difficulty at an earlier date—had erected two small houses of refuge, at Ath and Mons, to which the monks of Liessies might retire in such an emergency. In the end Blosius decided that it would be safest to leave Liessies, and after doing what he could to secure the Abbey from damage by appointing trustworthy guardians for it, he called upon his community to accompany him to Ath. Out of the whole number three only agreed to do so. The rest—little desirous of reform—preferred to take refuge in other monasteries : so, with his community reduced to three in number, Blosius retired to Ath.

Most men, in the Abbot’s place, would have been discouraged by such a desertion, but Blosius, from the first, seems to have seen the finger of God in his changed circumstances. On arriving at Ath, he greeted the humble priory, not as a place of exile, but as a refuge full of hope; and he at once began to instruct his tiny community in the Rule of St Benedict, which they now set themselves to observe, so far as their circumstances permitted, with the most minute exactness.

It was not long before the little band of refugees began to attract attention by the sanctity of their lives, and others came to Ath to submit themselves to the same discipline—among them some of the brethren from Liessies, moved to shame by their example. The holy Abbot, encouraged by these first successes, and hoping in time to win back the rest of his scattered flock, now conceived the plan of reducing Liessies to the rank of a priory only, transferring the abbacy to Ath, where a new monastery might be constructed, secure from foreign invasion. By this scheme, also, he could leave the les’s docile of his monks at Liessies, whilst he built up at Ath a new community prepared to lead a life of strict observance.

On the other hand, opposition to him was not wanting, even violence being resorted to by his enemies, who actually devastated the gardens of the priory, and cut the channels supplying it with water, in the hope of driving Blosius and his monks to leave Ath.

Ignoring these acts of malice, and encouraged by the progress of his community, which increased rapidly in numbers, the Abbot redoubled his efforts. He worked continually and with ardour, examining the works of the Fathers that his work might be based upon the rock of authority, translating them, and collecting materials for the treatise which was to be at once his apologia to his adversaries and the manifesto of his ideals to the world. What those ideals were, may be learned from this book, The Mirror For Monks.

Meanwhile the war ran its course, and, when peace was made, those of the Liessies community who had not joined Blosius at Ath returned to the Abbey. But they found themselves in a dilemma. If, on the one hand, they continued to live without their Abbot, they proved themselves to be in a state of hopeless relaxation, and ran the risk of seeing their monastery suppressed by authority. On the other hand, they dreaded the severe Rule and strict discipline which prevailed at Ath, and were afraid lest they might be compelled to submit to so drastic a reform.

As a way out of this perplexity they drew up a petition, addressed to Charles V, praying him to exert his authority and bring back Blosius with his religious to Liessies, the sad state of which they next described. They promised further that, if the Abbot would mitigate somewhat the severity of his Rule, they would submit themselves voluntarily to his authority; and concluded the whole by expressing their high regard for his personal character and sanctity.

The petition was well received, and, soon afterwards, Charles V issued orders to Blosius, telling him to return to Liessies. His command caused the Abbot much misgiving. “ He treated the question maturely,” say his biographers, “ between God and his own soul. After long reflection, he decided that it would be most to God’s glory if he gave way to the wishes of his religious at Liessies and to the orders of the Emperor.

He wrote, therefore, to the monks at the old monastery, saying that, since they were now convinced of the necessity for reform, they would be well advised to accept his, which he was prepared to moderate so far as certain grave men of known learning, whom he would consult, should advise. By this gracious promise, Louis won the goodwill of those who had hitherto opposed him.”

Blosius now returned to Liessies, and there, with the help of the learned men already mentioned, he drew up a series of Statutes or Constitutions, regulating in detail the observance to which the community should henceforth be bound. These, the Statutes of his Reform, were promulgated by him in the year 1539, and were subsequently approved and confirmed by a Bull of Pope Paul III, dated April 8, 1545.

Thus, after fifteen years of struggle, Blosius secured the end for which he had been working ever since he had become Abbot of Liessies; indeed, he did more than this. For the observance which he established in his monastery, and the Statutes in which it was crystallised, came to be regarded as a model, and thus exercised a wide influence on the Constitutions of the reformed Benedictine Congregations, founded in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

ASCETICAL and SPIRITUAL DOCTRINE

Benedictine abbot and spiritual writer; b. Donstienne (Flanders), 1506; d. Liessies, Jan. 7, 1566. Blosius was of the lesser nobility and, for a time, a page at the court of the Emperor Charles V, but at the age of 14 he entered the Benedictine abbey of Liessies in the Austrian Netherlands.

Discipline in this abbey was more or less relaxed, in a manner characteristic of the times. Blosius was regarded as an outstanding young man, and his old and well-meaning but weak abbot picked him as his successor. He was made coadjutor abbot in 1527, and in 1530 succeeded as abbot. Blosius found himself faced, not with the problem of extirpating grave scandals, but with that of revitalizing the whole spirit of the monastic life. Perhaps in his youthful ardor, he demanded too much too soon, but he seems to have come to terms with his community and turned it into a fervent one.

Blosius belonged to the contemplative tradition of the late Middle Ages; the ideal he held out before the soul was a continual sense, as far as was possible, of the presence of God. He did not as much lay stress upon achieving the ultimate union as is usual for writers in this tradition, but he was aware of it and described it in terms of Dionysian mysticism, as represented by the German school—Tauler and Suso. His program for the soul is meditation in a wide sense, interior conversations with the soul itself and with God—affective prayer. He knew that this depended on detachment from self-will in all its ramifications and conformity to the will of God. In the contemplative tradition, he made mortification consistent with this, and his teaching is excellent on that subject. As befits one whose life work was to turn a relaxed community into a fervent one, he understood the weakness of human nature.

Bibliography: Works, tr. b. a. wilberforce, 7 v. (London 1925–30), comprises all his original spiritual writings, although he also made florilegia and wrote a few small controversial works. A complete list of the many editions would be lengthy and difficult to compile. Acta Sanctorum Jan. 1:430–456. g. de blois, A Benedictine of the Sixteenth Century: Blosius, tr. lady lovat (London 1878).

Speculum Spirituale contains:

MONILE SPIRITUALE.

CORONA SPIRITUALE.

SCRINIOLVM SPIRITUALE.

|

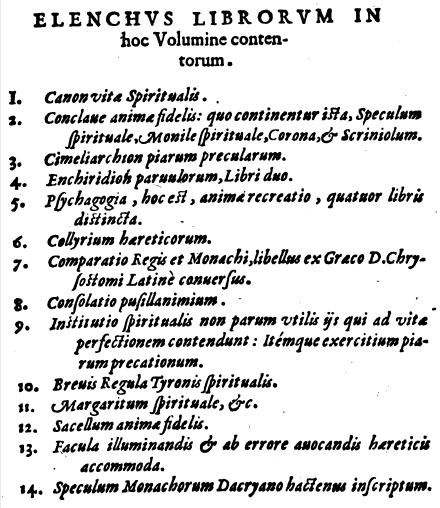

ELENCHUS LIBRORUM in Hoc Volumine contentorum 1. Canon Vitae Spiritualis 2. Conclave animae

fidelis: quo continentur ista, 3. Cimeliarchion piarum precularum 4. Enchiridion parvulorum, Libri duo 5. Psychagogia, hoc est anime recreatio, quatuor libris distincta. 6. Collyrium hareticorum 7. Comparatio Regis et Monachi, libellus ex Graco D.Chrysostomi Latine conversus. 8. Concolatio Pusillanissium 9. Institutio spiritualis non parumn utilis iis qui ad vitae perfectioum contendunt: itemque exercitium piarum preccationum. 10. Brevis Regula Tyronis spiritualis 11. Margaritum spirituale, etc. 12. Sacellum animae fidelis 13. Facula illuminandis [et] ab errore avocandis haereticis accommoda 14. Speculum Monachorum Dacryano hactenus inscriptum. |

xxxx» cont

|

|

|

|

|

|

This Webpage was created for a workshop held at Saint Andrew's Abbey, Valyermo, California in 1990