|

|

Viking Attack |

|

|

Viking Attack |

[adapted from Walker 4 and Logan 5]

[17.1] Viking Invasions; [17.2] Papal Decline and Renewal by the Revived Empire; [17.3] Reform Movements; [17.4] The Reform Party Secures the Papacy

[17.1]

VIKING

INVASIONS

[adapted from Logan 5]

A profound influence on historical Christianity was had by the warrior-seamen who left the islands and peninsulas of Scandinavia for overseas adventures and who gave their name to an epoch, the Viking Age. Out of fjords and viks (inlets) in their homelands, they sailed westward to the British Isles and further west to Iceland, Greenland and the shores of North America. They sailed southward, coursing through the river systems of the modern Low Countries and France. And they sailed eastward across the Baltic Sea and by river and portage [transporting their ships overland] reached deep into Russia.

|

|

| Viking Dragon Ship | Vikings Killing Christian |

They sailed as pagans, as worshippers of anthropomorphic deities like Thor, the thunder god, Odin, the god of the spear, and Frey, the god of sexual pleasure. Unexpectedly, in the years surrounding 800, Vikings first appeared, raiding the coast of the British Isles and the north-western continental mainland. The reasons lying behind this sudden eruption of these forces from the far north still divide historians, but an explanation that includes a population factor has much to commend it. In a culture with massive polygamy a crisis of population can occur within even one generation. Much evidence exists that at this time land in Scandinavia was being used increasingly for crops intended for human consumption and that marginal lands were being cultivated, both fairly clear indications of a growing human population. A population crunch may have occurred at the turn into the ninth century. Whatever the reasons, these peoples of the sea soon took to the seas in search of land. Except in Iceland and Greenland, it was already largely occupied land which they wanted and which they took only after violent encounters with native inhabitants, who were almost invariably Christians.

It is not without significance that among the very first known attacks was the fierce Viking raid on the monastery at Lindisfarne in Northumbria, defenceless and open to the seas. Under the year 793 the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle reports:

Dire portents appeared over Northumbria and sorely frightened the people. They consisted of immense whirlwinds and flashes of lightning, and fiery dragons were seen in the air. A great famine immediately followed these signs, and later in the same year, on 8th June, the ravages of heathen men miserably destroyed God’s church on Lindisfarne with plunder and slaughter.

A later writer, using near contemporary sources, likened this attack on Lindisfarne to ‘stinging hornets’ and ‘ravenous wolves’ and recounted that the Vikings slew priests and nuns and destroyed everything in sight, including holy relics, and took with them some monks as slaves. Even the far-off Alcuin, the native Northumbrian by then in Francia, wrote seven letters in response to news of this raid. In the following year the Vikings were at Jarrow. Yet these were but incidents in larger movements. The Vikings were soon in the Orkney and Shetland islands and sailed down the west coast of Britain. In 794 they attacked the Hebrides and the famous island monastery at Iona. In the next year—these were summer raids—they attacked Iona again and the island of Skye and, across the Irish Sea, the island of Lambay, just north of Dublin, and even islands off the west coast of Ireland.

|

|

| Iona | Iona Abbey |

Iona was attacked yet again in 802 and 806, and in the latter raid sixty-eight Irish monks were slain and the survivors abandoned Columba’s monastery for Kells on the Irish mainland. And so the raids on Ireland continued not always against monastic sites but with a chilling regularity. In 823 they attacked Skellig Michael, the monastic sanctuary perched on rocks eight miles off the Kerry coast, and, at the other end of the island, the monastery at Bangor, Co. Down, where the relics of St Comgall were desecrated. In 832 alone the monastery at Armagh was attacked three times in one month. At about this same time Vikings gained access to the Irish heartland, sailing up the River Shannon, attacking the monastery at Clonmacnois. In 839 they burned the monastery at Cork.

|

|

| Skellig Michael | Monastic Cells/Beehive Huts on Skellig Michael |

Such raids—and many others could be added to this litany of devastating attacks—were not against monasteries as monasteries (i.e., as places of Christian worship) but against monasteries as keepers of gold and silver vessels and as places containing prominent men, who could be held for ransom. Undefended monasteries were obvious targets. Both in Ireland and in England the Vikings were frequently referred to simply as ‘heathens’.

Attacks by these ‘heathens’ were not confined to the British Isles. By 834 they were attacking in large numbers at Dorestad, the great entrepot situated where the Rhine and Lek then met, at the modern Wijk in the Netherlands, and they were there again in each of the next three years. The Vikings were soon penetrating the river systems of modern France and the Low Countries. Viking ships sailed up the Schelde in 836 and set fire to Antwerp. Their ships sailed into the Loire in 834, attacking the monastic island of Noirmoutier at the river mouth. They soon used it as a base for raids upriver: in 843 they reached Nantes, where, on the feast of St John the Baptist (24 June), they seized the bishop and slew him at the altar of his cathedral. And it was at Nantes, if we can believe later chronicles, that a scene of utter barbarity ensued. The Vikings killed whom they willed in a butchery of epic proportions, stopping only when, dripping with blood and laden with bloodied jewels, they returned to Noirmoutier.

|

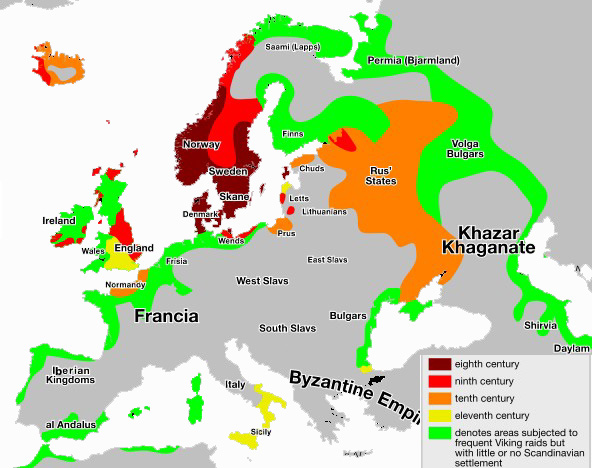

| Viking Raids and Settlements 750-1050. Map from Wikimedia Commons |

Other Vikings sailed up the Seine, where, in 841, they attacked Rouen and then the monastery of Jumièges, before seizing the monastery of St Wandrille and holding it for ransom. They harassed Paris and, later, in the 880s, besieged the town for a full year. And they were in other rivers: the Meuse, Scheldt, Somme and Dordogne. One contemporary lamented

The fleets grow larger and the Vikings themselves grow and grow in number. On all sides Christian people suffer massacre and burning and plunder… The Vikings crush everything in their path: there is no defense. They capture Bordeaux, Périgeux, Limoges, Angoulême and Toulouse. They destroy Angers, Tours and Orléans… Ships beyond counting sail up the Seine, where evil prevails. Rouen is attacked, pillaged and burnt; Paris, Beauvais and Meaux are seized; the stronghold of Melun is razed; Chartres is occupied; Evreux and Bayeux are pillaged; and all the towns are attacked.

Monks, unprepared for such attacks, fled from such monasteries as St Maixent, Charroux, St Maur-sur-Loire and St Martin of Tours. For two generations fleeing monks could be seen on the roads leading to Burgundy, the Auvergne and Flanders, taking with them their ‘saints’, the canons of Tours carrying away the body of St Martin at least four times from the attacking heathens.

VIKINGS in BRITAIN CONVERT to CHRISTIANITY

When peace was made with the Vikings, it was everywhere accompanied by the conversion of the heathens to Christianity. After the defeat of the Danes by King Alfred at Edington in 878, Guthrum, the Viking leader, whose army was still intact and still a threat, accepted baptism, and the conversion of his followers no doubt followed. When, in the following year, these Vikings crossed the country to ‘share’ out East Anglia, they did so as Christians. And, in the north of England, when the Viking king Guthfrith died c.895, he was buried beneath York Minster with full Christian rites. Integration in England was fairly swift. For example, Oda, archbishop of Canterbury (941-48), was the son of a Danish settler who had converted to Christianity. Thus Oda’s nephew, St Oswald, the great monastic reformer, was the grandson of a pagan Viking. Three generations from hammer to cross: by any measure a rapid assimilation.

In Ireland, the tale that Brian Boru’s Irish Christian army defeated the Viking pagan army at the Battle of Clontarf on Good Friday, 1014, and that the defeated Vikings accepted Christian baptism has much of fancy about it. There was a Battle of Clontarf on that day, but it was not between the Irish and the Vikings, between the Christians and the heathens: the battle was between two Irish factions, each of which had Viking contingents in its army. The process of assimilation in Ireland had already begun in the late ninth century with the intermarriage of some Viking leaders and Irish princesses, accompanied by the Vikings’ conversion. Such marriages became more frequent from c.950 and continued apace both before and after Clontarf. In 1169, when other strangers came, they could not identify the Vikings, so complete was their assimilation: they were indistinguishable from the native Irish Catholics.

VIKINGS in FRANCIA CONVERT to CHRISTIANITY

The situation in Francia warrants close examination. At least three attempts were made by the Vikings to establish permanent settlements. Only one was successful, in the lower Seine, and it is this part of Francia that still bears their name, Normandy. The exact date is not clear, but it was probably in 911 that the West Frankish king, Charles the Simple, made an agreement with the Viking leader, Rollo. The latter was allowed to settle that probably underpopulated region, and, in return, he became a Christian and promised to defend the lower Seine from future attacks, apparently from the Bretons and from other Vikings. Intermarriage between newly baptized Viking men and Christian Frankish women must have quickly followed. The Vikings took new, Christian names: Rollo became Robert; his daughter Geloc became Adèle; Thurstein of the Contentin became Richard; Stigand of Mézidon became Odo; and so forth. The son of Rollo, William Longsword, became so fervent a Christian that he had to be restrained from becoming a monk so that he could succeed his father. He married a Christian princess and his sister married a Christian prince. So swift was this integration that Williams son (Rollos grandson) had to be sent from Rouen to Bayeux to learn Viking ways. Thus in less than twenty-five years the Viking capital at Rouen was a French-speaking city. The younger sons of Norman lords who were to land in southern Italy and Sicily in the decades after 1016 were French, as was the Norman duke who was to sail with his army to England in 1066. The lords of Normandy were to establish monasteries, to lead the reforming movements of the eleventh century and, later, to be in the front ranks of Christian warriors who went to the Holy Land on crusade. The conversion and assimilation of the northmen in Francia proved to have a significant impact on the future of the medieval church.

VIKING EXPLORERS and SETTLERS

An appraisal of the Vikings that stops here would tell only part of the story. Perhaps the most fascinating aspects of their achievements took place far, far west from the Seine estuary. Beyond Ireland and Scotland and the islands to the north, Viking sailors discovered the empty land they called Iceland, empty, that is, except for Irish monks who lived in the south-west during summer seasons. Settlement on this land, the size of Ireland, followed almost immediately, and in the sixty years from 870 to 930 a substantial migration took place, principally from Norway itself but also from Norse settlements in the nearer Celtic lands, including some Celts, many of them slaves. It was a migration numbering in the tens of thousands, perhaps near 30,000. There was no assimilation needed, and their Christianization came from their Norse homeland. Tales were told that a sudden volcanic eruption in the year 1000 led the settlers to accept Christianity. More prosaically, mass conversion did take place in the year 1000 but came through two Icelandic chieftains, who had been converted at the court of King Olaf, who, as a Christian, had become king of Norway in 995. They were sent back to Iceland to establish Christianity as the official religion of the land. And, so, Gizur, a converted chieftain missionary, attended the general assembly held at their outdoor meeting place, the Law Rock. He and his supporters demanded official acceptance of the Christian religion. For twenty-four hours the Law Speaker pondered the issues and decreed that there should be but one religion in Iceland. All people should be baptized and should publicly be Christians, but, if they wished, they could privately be heathen. Heathenism soon faded away. Bishops were appointed at Skalholt (1056) and at Holar (1106). A codification of canon law was made in 1123, seventeen years before Gratian produced his Decretum at Bologna.

Beyond Iceland to the west the Vikings sailed, and not far behind them came the Christian religion. From western Iceland in 985 Eric the Red set sail westward for almost 450 miles, when he caught sight of an enormous land mass with imposing glaciers reaching to a height of 1,900 metres. He turned south, following the coast around Cape Farewell, east of which he found green, rich-looking land on deep fjords, reaching out from the mountains, a sight clearly reminiscent of Norway. Two settlements were made: one in the extreme south-west (the Eastern Settlement) and the other four hundred miles further north along the western coast (the Western Settlement). In a practice not unknown to modern land developers, Eric called this glaciered land ‘Greenland’. In truth, the land in the south-west where the settlements lay was verdant and warmer then than now. Greenland’s conversion to Christianity came as a result of the conversion of Iceland and, also, about the year 1000. The Eric Saga relates,

Eric was loath to leave the old religion, but his wife, Thjodhild, was converted at once and had a church built at a distance from the farmstead, which was called Thjodhild s church. It was there that she and other converts would go to pray. Thjodhild refused to live with her husband after her conversion, and this greatly displeased him.

His displeasure might have abated as, in time, Eric too probably became a Christian. The Christian church flourished in Greenland. A diocese with a cathedral and a resident bishop was established at Gardar near Eiriksfjord in 1126, and bishops from Greenland travelled to Europe for ecumenical councils. A monastery of Augustinian canons and a nunnery of Benedictine nuns were both founded in the twelfth century. A total of twelve parish churches in the Eastern Settlement and four parish churches in the Western Settlement are signs of a vital, if small, Christian community. A thirteenth-century Norse book (King’s Mirror) commented,

The peoples in Greenland are few in number, since only part of the land is free enough from ice for human habitation. They are a Christian community with their own churches and priests. By comparison to other places it would form probably a third of a diocese: yet the Greenlanders have their own bishop owing to their distance from other Christian people.

For over four hundred years these two settlements were the westernmost part of the medieval, European, Christian world. And it ended sometime before 1500 without witnesses, its demise a historical puzzle. An explanation stressing severe climatic cooling and hostile relations with displaced native peoples might be near the mark. Writing in 1492, Pope Alexander VI spoke of a dimly remembered outpost of Christendom:

The diocese of Gardar lies at the ends of the earth in the land called Greenland… It is reckoned that no ship has sailed there for eighty years and that no bishop or priest has resided there during this period. As a result, many inhabitants have abandoned the faith of their Christian baptism: once a year they exhibit a sacred linen used by the last priest to say Mass there about a hundred years ago.

The Vikings also reached into areas to the east of their northern homelands, but that story runs beyond the limits of this book.

|

| Viking Raids and Settlements 750-1050. Map from Wikimedia Commons |

VIKING CONVERSIONS in SCANDINAVIA

Ironically more is known about the conversion process of Vikings who journeyed abroad than about the conversion of their kinsmen who stayed home. A few mileposts can be seen, but much of the northern landscape lies in a historical mist. Denmark was visited in the eighth century by Willibrord with no success and in the ninth century by Ansgar only with limited success. The conversion of the Danish people occurred through the conversion of their king, Harald Bluetooth (c.960-c.987). His mother was Christian but his father a resolute pagan. It was probably upon becoming king that Harold accepted baptism. An early legend has it that a German missionary came to his court and a debate ensued. The Danes would accept Christ in their pantheon of God, it was argued, but just as one of many gods and as a god decidedly inferior to the chief gods. The missionary asserted one God and three divine persons. One might wonder how the theological subtleties of the doctrine of the Trinity sounded to Danish ears. In any case, the story runs that the missionary would be believed if he could pass the ordeal of fire. He placed his bare hand in a glove heated by fire. When he withdrew his hand, it was seen to have been unaffected by the ordeal, and Harald thereupon took baptism and decreed that Christianity was to be the sole religion of his kingdom. It is not only the cynical who can see here in the conversion of Harald a possible political motivation—a smoother relationship with the German emperor Otto. At Jelling, midway up the Danish peninsula, two remarkable stones stand as witnesses to the conversion of Denmark. One, the smaller, was erected by Gorm (Harald’s father) to his wife; it bears the inscription: ‘King Gorm did this in memory of his wife, Thyri, glory of Denmark.’ No mention of her being a Christian and certainly no Christian symbols. The other, a larger stone about eight feet tall, contains a large figure of Christ and this inscription: ‘King Harold had this stone made in memory of his father, Gorm, and his mother, Thyri, the same Harald who conquered all Denmark and Norway and who made the Danes Christian.’ A simple act of state and the Danes were officially Christian, but the pastoral process of instruction in the new ways lies beyond our view.

Norway’s conversion followed in the first third of the eleventh century, and, again, a king was involved or, rather, two kings, each called Olaf. The first, Olaf Tryggvason, fought in England in the last wave of Viking attacks, which began in the 990s. There in England, in 994, he became a Christian, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle tells us, as part of a peace settlement after extensive raids in south-eastern England, and the English King Etheldred stood sponsor at Olaf’s confirmation. Olaf returned home, probably in 995, intent on seizing the crown of Norway and converting his people to the Christian faith. He succeeded in the former and ruled Norway until 1000, but he only partially succeeded in the latter, and this success, as we have seen, was felt as far west as Iceland and Greenland. It was another Olaf—Olaf Haraldsson (1025-30), known to history as St Olaf—who made Norway Christian. Saint though he may be, his methods were far from benign: in Professor Jones’s words, ‘he executed the recalcitrant, blinded or maimed them, drove them from their homes, cast down their images and marred their sacred places.’ Olaf organized a church which, at first, was to have bishops subject to the archbishop of Bremen, but, in time, Norway had its own archbishop at Trondheim, site of St Olaf’s tomb, and the archbishop’s jurisdiction extended as far west as the tiny diocese of Gardar in Greenland.

What happened in Sweden cannot be described in terms similar to those used to describe the conversion process in Denmark and Norway, namely, a king’s conversion followed by his people’s conversion. Sweden was different. It is true that a Swedish king called Olaf received baptism at the hands of an English missionary in 1008 and that his daughter married the converted King Olaf of Norway. Yet the conversion of the Swedish people did not follow. A long process of at least a century followed. Large areas of Sweden remained loyal to old gods and old ways. At Uppsala, site of a great pagan temple, worship and sacrifice (even human sacrifice) continued into the next century. Writing c.1075, Adam of Bremen recounts,

It is customary to solemnize in Uppsala, at nine-year intervals, a general feast of all the provinces of Sweden. From attendance at this festival no one is exempted. Kings and people all and singly send their gifts to Uppsala and, what is more distressing than any kind of punishment, those who have already adopted Christianity redeem themselves through these ceremonies.

A diocese was established at Sigtuna, but in 1060 the bishop was driven out. Twenty years later the Christian King Inge refused to worship at Uppsala and had to flee for his life. In the opening years of the twelfth century the temple of Uppsala was destroyed and a Christian church, still surviving, rose on its site at what is now Old Uppsala.

Our story has taken us far into the future, beyond our general narrative. It is time now to return there to look at the state of the Christian religion more generally at the time of the break-up and, indeed, breakdown of the Carolingian synthesis and after. Back to Europe of the mid-ninth century.

Further reading

For general works on the Vikings see Gwyn Jones, A History of the Vikings (2nd edn; Oxford, 1984), F. Donald Logan, The Vikings in History (2nd edn; London, 1991) and Peter Sawyer (ed.), The Oxford Illustrated History of the Vikings (Oxford, 1997). A useful work of reference is Phillip Pulsiano (ed.), Medieval Scandinavia: An Encyclopedia (New York, 1993). For Iceland the standard work is Dag Strömbäck, The Conversion of Iceland: A Survey (Viking Society for Northern Research, 1975), to which should be added Jenny Jochens, ‘Late and Peaceful: Iceland’s Conversion through Arbitration in 1000’, Speculum 74 (1999), 621-55, and Orri Vésteinsson, The Christianization of Iceland: Priests, Power,and Social Change, 1000-1300 (Oxford, 2000). For Greenland two works stand out: Finn Gad, The History of Greenland, vol. 1, Earliest Times to 1700 (London, 1970), and Kirsten A. Seaver, The Frozen Echo (Stamford, 1996). A book of much helpful detail is Tore Nyberg, Monasticism in North-Western Europe, 800-1200 (Aldershort, Hants, and Burlingon, VT, 2000).

[17.2]

PAPAL

DECLINE

and

RENEWAL

by

THE

REVIVED

EMPIRE

It may seem strange that the papacy which showed such power under Nicholas I should within twenty-five years of his death have fallen into its lowest degradation. The explanation is the growing anarchy of the times. Up to a certain point the collapse of the empire aided the development of papal authority; that passed, the papacy became the sport of the Italian nobles and ultimately of whatever faction was in control of Rome, since the Pope was chosen by the clergy and people of the city. The papacy could now appeal for aid to no strong outside political power as Zacharias had to Pippin against the Lombards.

Pope Stephen VI condemns the deceased Pope Formosus

At the close of the ninth century the papacy was involved in the quarrels for the possession of Italy.

[POPE] Stephen V (885- 891) was overborne by Guido, duke of Spoleto, and compelled to grant him the empty imperial title.

[POPE] Formosus (891-896) was similarly dependent, and crowned Guido’s son, Lambert, Emperor in 892.

From this situation [POPE] Formosus sought relief in 893 by calling in the aid of Arnulf, whom the Germans had chosen King in 887.

In 895 Arnulf captured Rome, and was crowned Emperor by [POPE] Formosus the next year.

|

|

|

| Pope Stephen VI | The "Trial" of Pope Formosus' corpse at the "Cadaver Synod" in 897 |

A few months later Lambert was in turn master of Rome,

and his partisan, [POPE] Stephen VI (896-897), had the remains of the lately deceased Formosus disinterred, condemned in a synod, and treated with extreme indignity.

A riot, however, thrust [POPE] Stephen VI into prison, where he was strangled.

Popes now followed one another in rapid succession, as the various factions controlled Rome. Between the death of Stephen VI (897) and the accession of John XII (955) no less than seventeen occupied the papal throne. The controlling influences in the opening years of the tenth century were those of the Roman noble Theophylact, and his notorious daughters, Marozia and Theodora. The Popes were their creatures. From 932 to his death in 954 Rome was controlled by Marozia’s son Alberic, a man of strength, ability, and character, who did much for churchly reforms in Rome, but nevertheless secured the appointment of his partisans as Popes.

|

|

|

| Marozia | Crown of Otto I | Otto II Invests Adalbert, Bp. of Prague |

On his death he was succeeded as temporal ruler of Rome by his son Octavian, who had few of the father’s rough virtues. Though without moral fitness for the office, Octavian secured his own election as Pope in 955, choosing as his name in this capacity John XII (955-964), being one of the earliest Popes to take a new name on election. He altered the whole Roman situation and introduced a new chapter in the history of the papacy, by calling for aid upon the able German sovereign, Otto I, against the threatening power of Berengar II, who had gained control of a large part of Italy.

The Regeneration of Germany - OTTO I (936- 973)

The line of Charlemagne came to an end in Germany, in 911, with the death of Louis the Child. With the disintegration of the Carolingian empire and the growth of feudalism, Germany threatened to fall into its tribal divisions, Bavaria, Swabia, Saxony, Franconia, and Lorraine. The most powerful men were the tribal dukes. The necessities of defense from the Northmen and Hungarians forced a degree of unity, which was aided by the jealousy felt by the bishops of the growing power of the secular nobility.

In 911 the German nobles and great clergy, therefore, chose Conrad, duke of Franconia, as King (911-918).

He proved inadequate, and in 919 Henry the Fowler, duke of Saxony, was elected his successor (919-936). His ability was equal to the situation. Though having little power, save in Saxony, he secured peace from the other dukes, fortified his own territories, drove back the Danes, subdued the Slavs east of the Elbe, and finally, in 933, defeated the Hungarian invaders. The worst perils of Germany had been removed, and the foundations of a strong monarchy laid, when he was succeeded as King by his even abler son, Otto I (936- 973).

|

|

|

| Otto I, Modern German Mosaic (1903) |

Octagonal Imperial Crown of Otto 1 worn over a miter |

Otto’s first work was the consolidation of his kingdom. He made the semi-independent dukes effectively his vassals. In this work he used above all the aid of the bishops and great abbots. They controlled large territories of Germany, and by filling these posts with his adherents, their forces, coupled with his own, were sufficient to enable Otto to control any hostile combination of lay nobles. He named the bishops and abbots, and under him they became, as they were to continue to the Napoleonic wars, lay rulers as well as spiritual prelates. The peculiar constitution of Germany thus arose, by which the imperial power was based on control of ecclesiastical appointments—a situation which was to lead to the investiture struggle with the papacy in the next century. As Otto extended his power he founded new bishoprics on the borders of his kingdom, partly political and partly missionary in aim, as Brandenburg and Havelberg among the Slavs, and Schleswig, Ripen, and Aarhus for the Danes. He also established the archbishopric of Magdeburg.

Had Otto confined his work to Germany it would have been for the advantage of that land, and for the permanent upbuilding of a strong central monarchy. He was, however, attracted by Italy, and established relations there of the utmost historic importance, but which were destined to dissipate the strength of Germany for centuries. A first invasion in 951 made him master of northern Italy. Rebellion at home (953) and a great campaign against the Hungarians (955) interrupted his Italian enterprise; but in 961 he once more invaded Italy, invited by Pope John XII, then hard pressed by Berengar II . On February 2, 962, Otto was crowned in Rome by John XII as Emperor—an event which, though in theory continuing the succession of the Roman Emperors from Augustus and Charlemagne, was the inauguration of the Holy Roman Empire, which was to continue in name till 1806.

|

|

|

| Otto I, Bamberg | Otto II Invests Adalbert as Bishop of Prague |

Theoretically, the Emperor was the head of secular Christendom, so constituted with the approval of the church expressed by coronation by the papacy. Practically, he was a more or less powerful German ruler, with Italian possessions, on varying terms with the Popes.

John XII soon tired of Otto’s practical control, and plotted against him. Otto, of strong religious feeling, to whom such a Pope was an offense, doubtless was also moved by a desire to strengthen his hold on the German bishops by securing a more worthy and compliant head of the church. In 963 Otto compelled the Roman people to swear to choose no Pope without his consent, caused John XII to be deposed, and brought about the choice of Leo VIII (963-965). The new Pope stood solely by imperial support. On Otto’s departure John XII resumed his papacy, and on John’s death the Roman factions chose Benedict V. Once more Otto returned, forced Benedict into exile, restored Leo VIII, and after Leo’s speedy demise, caused the choice of John XIII (965-972). Otto had rescued the papacy, for the time being, from the Roman nobles, but at the cost of subserviency to himself.

OTTO’S son and successor, Otto II (973-983), pursued substantially the same policy at home, and regarding the papacy, as his father, though with a weaker hand.

|

|

|

| Otto II in Glory | Otto II Anointed by Christ (982) |

His son, Otto III (983-1002), went further. The Roman nobles had once more controlled the papacy in his minority, but in 996 he entered Rome, put them down, and caused his cousin Bruno to be made Pope as Gregory V (996-999)—the first German to hold the papal office. After Gregory’s decease Otto III placed on the papal throne his tutor, Gerbert, archbishop of Rheims, as Silvester II (999-1003)—the first French Pope, and the most learned man of the age.

|

|

| Henry II crowned by Christ (Sacramentary, c.1010) |

The death of Otto III ended the direct line of Otto I, and the throne was secured by Henry II (1002-1024), duke of Bavaria and great-grandson of Henry the Fowler. A man filled with sincere desire to improve the state of the church, he yet felt himself forced by the difficulties in securing and maintaining his position to exercise strict control over ecclesiastical appointments. His hands were too fully tied by German affairs to interfere effectually in Rome. There the counts of Tusculum gained control of the papacy, and secured the appointment of Benedict VIII (1012-1024), with whom Henry stood on good terms, and by whom he was crowned. Henry even persuaded the unspiritual Benedict VIII at a synod in Pavia in 1022, at which both Pope and Emperor were present, to renew the prohibition of priestly marriage and favor other measures which the age regarded as reforms.

With the death of Henry II the direct line was once more extinct, and the imperial throne was secured by a Franconian count, Conrad II (1024-1039), one of the ablest of German rulers, under whom the empire gained great strength. His thoughts were political, however, and political considerations determined his ecclesiastical appointments. With Rome he did not interfere. There the Tusculan party secured the papacy for Benedict VIII’s brother, John XIX (1024-1032), and on his death for his twelve-year-old nephew, Benedict IX (1033-1048), both unworthy, and the latter one of the worst occupants of the papal throne. An intolerable situation arose at Rome, which was ended by Conrad’s able and far more religious son, Henry III, Emperor from 1039 to 1056.

[17.3]

REFORM

MOVEMENTS

Charlemagne himself valued monasticism more for its educational and cultural work than for its ascetic ideals. Those ideals appealed, however, in Charlemagne’s reign to a soldier- nobleman of southern France, Witiza, or as he was soon known, Benedict (750?-821) called of Aniane, from the monastery founded by him in 779. Benedict’s aim was to secure everywhere the full ascetic observation of the “Rule” of Benedict of Nursia. The educational or industrial side of monasticism appealed little to him. He would raise monasticism to greater activity in worship, contemplation, and self- denial. Under Louis the Pious Benedict became that Emperor’s chief monastic adviser, and by imperial order, in 816 and 817, Benedict of Aniane’s interpretation of the elder Benedict’s Rule was made binding on all monasteries of the empire. Undoubtedly a very considerable improvement in their condition resulted. Most of these benefits were lost, however, in the collapse of the empire, in which monasticism shared in the common fall.

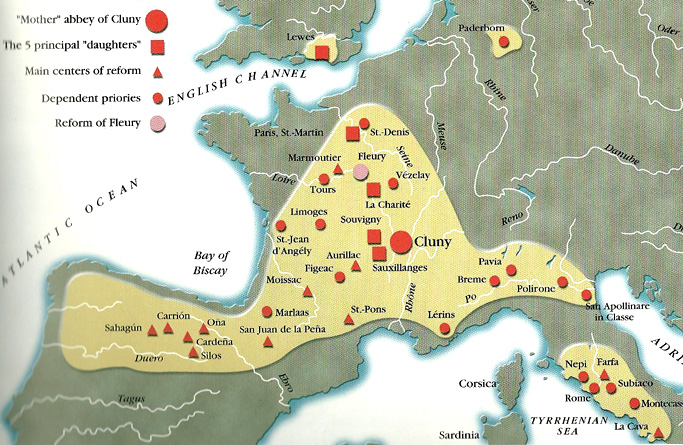

Cluny

The misery of the times itself had the effect of turning men’s minds from the world, and of magnifying the ascetic ideal. By the early years of the tenth century a real ascetic revival of religion was beginning that was to grow in strength for more than two centuries. Its first conspicuous illustration was the foundation in 910 by Duke William the Pious, of Aquitaine, of the monastery of Cluny, not far from Macon in eastern France. [1] Cluny was to be free from all episcopal or worldly jurisdiction, self-governing, but under the protection, of the Pope. Its lands were to be secure from all invasion,or secularization, and its rule that of Benedict, interpreted with great ascetic strictness.

|

|

| Cluny | Cluny |

Cluny was governed by a series of abbots of remarkable character and ability. Under the first and second of these, Berno (910-927) and Odo (927-942), it had many imitators, through their energetic work. Even the mother Benedictine monastery of Monte Cassino, in Italy, was reformed on Cluny lines, and, favored by Alberic, a monastery, St. Mary on the Aventine hill, was founded which represented Cluny ideas in Rome. By the death of Odo the Cluny movement was wide-spread in France and Italy.

It was no part of the original purpose of Cluny to bring other monasteries into dependence on it, or to develop far- reaching churchly political plans. Its aim was a monastic reformation by example and influence. Yet even at the death of the first abbot five or six monasteries were under the control of the abbot of Cluny. Under the fifth abbot, Odilo (994-1048), however, Cluny became the head of a “congregation,” since he brought all monasteries founded or reformed by Cluny into dependence on the mother house, their heads being appointed by and responsible to the abbot of Cluny himself.

This was new in monasticism, and it made CIuny practically an order, under a single head, with all the strength and influence that such a constitution implies. It now came to have a force comparable with that of the Dominicans or Jesuits of later times. With this growth came an enlargement of the reformatory aims of the Cluny movement. An illustration is the “Truce of God.” Though not originated by Cluny, it was taken up and greatly furthered by Abbot Odilo from 1040 onward. Its aim was to limit the constant petty wars between nobles by prescribing a closed season in memory of Christ’s passion, from Wednesday evening till Monday morning, during which acts of violence should be visited with severe ecclesiastical punishments. Its purpose was excellent; its success but partial.

As the Cluny movement grew it won the support of the clergy, and became an effort, not for the reform of monasticism, as at first, but for a wide-reaching betterment of clerical life.

By the first half of the eleventh century the Cluny party, as a whole, stood in opposition to “Simony”[2] and “Nicolaitanism.”[3]

By the former [Simony] was understood any giving or reception of a clerical office for money payment or other sordid consideration.

By the latter [Nicolatianism], any breach of clerical celibacy, whether by marriage or concubinage.

These reformers desired a worthy clergy, appointed for spiritual reasons, as the age understood worthiness. While many of the Cluny party, and even abbots of Cluny itself, had apparently no criticism of royal ecclesiastical appointments, if made from spiritual motives, by the middle of the eleventh century a large section was viewing any investiture by a layman as simony, and had as its reformatory ideal a papacy strong enough to take from the Kings and princes what it deemed their usurped powers of clerical designation. This was the section that was to support Hildebrand in his great contest.

ELSEWHERE than in the Cluny movement ascetic reform was characteristic of the tenth and eleventh centuries. In Lorraine and Flanders a monastic revival of large proportions was instituted by Gerhard, abbot of Brogne (?-959).

|

|

| Romuald | Camaldoli |

IN Italy, Romuald of Ravenna (950?-1027) organized settlements of hermits, called “deserts,” in which the strictest asceticism was practised, and from which missionaries and preachers went forth. The most famous “desert,” which still exists and gave its name to the movement, is that of Camaldoli, near Arezzo. Even more famous was Peter Damian (1007?-1072), likewise of Ravenna, a fiery supporter of monastic reform, and opponent of simony and clerical marriage, who was, for a time, cardinal bishop of Ostia, and a leading ecclesiastical figure in Italy in the advancement of Hildebrandian ideas, preceding Hildebrand’s papacy.

Henry III Rescues the Papacy BY DOMINATING IT COMPLETELY

It is evident that before the middle of the eleventh century a strong movement for churchly reform was making itself felt. Henry II had, in large measure, sympathized with it. Henry III (1039-1056) was even more under its influence.

|

|

| Henry III | Clement II |

Abbot Hugh of Cluny (1049-1109) was a close friend of that Emperor, while the Empress, Agnes, from Aquitaine, had been brought up in heartiest sympathy with the Cluny party, of which her father had been a devoted adherent. Henry III was personally of a religious nature, and though he had no hesitation in controlling ecclesiastical appointments for political reasons as fully as his father, Conrad II, he would take no money for so doing, denounced simony, and appointed bishops of high character and reformatory zeal.

Bizarre Scandals in Rome

The situation in Rome demanded Henry III’s interference, for it had now become an intolerable scandal.

[1] Benedict IX, placed on the throne by the Tusculan party, had proved so unworthy that its rivals, the nobles of the Crescenzio faction, were able to drive him out of Rome, in 1044,

[2] and install their representative as Silvester III in his stead.

Benedict, however, was soon back in partial possession of the city, and now, tiring temporarily of his high office, and probably planning marriage, he sold it in 1045 for a price variously stated as one or two thousand pounds of silver.

[3] The purchaser was a Roman archpriest of good repute for piety, John Gratian, who took the name Gregory VI. Apparently the purchase was known to few. Gregory was welcomed at first by reformers like Peter Damian. The scandal soon became public property.

Benedict IX refused to lay down the papacy, and there were now three Popes in Rome, each in possession of one of the principal churches, and each denouncing the other two.

Henry III now interfered. At a synod held by him in Sutri in December, 1046,

[1] Silvester III was deposed,

[2] and Gregory VI compelled to resign and banished to Germany.

[3] A few days later, a synod in Rome, under imperial supervision, deposed Benedict IX.

Henry III immediately nominated and the overawed clergy and people of the city elected a German, Suidger, bishop of Bamberg, as Clement II (1046-1047), who crowned Henry III as Emperor..

Henry III had reached the high-water mark of imperial control over the papacy. So grateful did its rescue from previous degradation appear that the reform party did not at first seriously criticise this imperial domination; but it could not long go on without raising the question of the independence of the church. The very thoroughness of Henry’s work soon roused opposition.

Henry III had repeated occasion to show his control of the papal office. Clement II soon died, and Henry caused another bishop of his empire to be placed on the papal throne as Damasus II. The new Pope survived but a few months. Henry now appointed to the vacant see his cousin Bruno, bishop of Toul, a thoroughgoing reformer, in full sympathy with Cluny, who now journeyed to Rome as a pilgrim, and after merely formal canonical election by the clergy and people of the city—for the Emperor’s act was determinative—took the title of Leo IX (1049-1054).

[17.4]

THE

REFORM

PARTY

SECURES

THE

PAPACY

Leo IX set himself vigorously to the task of reform. His most effective measure was a great alteration wrought in the composition of the Pope’s immediate advisers—the cardinals. The name, cardinal, had originally been employed to indicate a clergyman permanently attached to an ecclesiastical position. By the time of Gregory I (590-604), its use in Rome was, however, becoming technical.

[1] From an uncertain epoch, but earlier than the conversion of Constantine, in each district of Rome a particular church was deemed, or designated, the most important, originally as the exclusive place for baptisms probably. These churches were known as “title” churches, and their presbyters or head presbyters were the “cardinal” or leading priests of Rome.

[2] In a similar way, the heads of the charity districts into which Rome was divided in the third century were known as the “cardinal” or leading deacons.

[3] At a later period, but certainly by the eighth century, the bishops in the immediate vicinity of Rome, the “suburbicarian” or suburban bishops, were called the “cardinal bishops.”

This division of the college of cardinals into “cardinal bishops,” “cardinal priests,” and “cardinal deacons” persists to the present day. As the leading clergy of Rome and vicinity, they were, long before the name “cardinal” became exclusively or even primarily attached to them, the Pope’s chief aids and advisers.

On attaining the papacy Leo IX found the cardinalate filled with Romans, and so far as they were representative of the noble factions which had long controlled the papacy before Henry III’s intervention, with men unsympathetic with reform. Leo IX appointed to several of these high places men of reformatory zeal from other parts of Western Christendom. He thus largely changed the sympathies of the cardinalate, surrounded himself with trusted assistants, and in considerable measure rendered the cardinalate thenceforth representative of the Western Church as a whole and not simply of the local Roman community. It was a step of far-reaching consequence.

THREE IMPORTANT REFORMERS:

Three of these appointments were of special significance.

Humbert, a monk of Lorraine, was made cardinal bishop, and to his death in 1061 was to be a leading opponent of lay investiture and a force in papal politics.

Hugh the White, a monk from the vicinity of Toul, who was to live till after 1098, became a cardinal priest, was long to be a supporter of reform, only to become for the last twenty years of his life the most embittered of opponents of Hildebrand and his successors.

Finally, Hildebrand himself, who had accompanied Leo IX from Germany, was made a sub-deacon, charged with the financial administration, in some considerable measure, of the Roman see. Leo IX appointed other men of power and reformatory zeal to important, if less prominent, posts in Rome and its vicinity.

Hildebrand, who now came into association with the cardinalate, is the most remarkable personality in mediaeval papal history. A man of diminutive stature and unimpressive appearance, his power of intellect, firmness of will, and limitlessness of design made him the outstanding figure of his age. Born in humble circumstances in Tuscany, not far-from the year 1020, he was educated in the Cluny monastery of St. Mary on the Aventine in Rome, and early inspired- with the most radical of reformatory ideals. He accompanied Gregory VI to Germany on that “unlucky Pope’s banishment , and thence returned to Rome with Leo IX. Probably he was already a monk, but whether he was ever in Cluny itself is doubtful. He was, however, still a young man, and to ascribe to him the leading influence under the vigorous Leo IX is an error. Leo was rather his teacher.

Leo IX. East and West Divided [The Great Schism]

Leo IX entered vigorously on the work of reform. He stood in cordial relations with its chief leaders, Hugo, abbot of Cluny, Peter Damian, and Frederick of Lorraine. He made extensive journeys to Germany and France, holding synods and enforcing papal authority. At his first Easter synod in Rome, in 1049, he condemned simony and priestly marriage in the severest terms.

A synod held under his presidency in Rheims the same year affirmed the principle of canonical election, “no one shall be promoted to ecclesiastical rulership without the choice of the clergy and people.” By these journeys and assemblies the influence of the papacy was greatly raised.

In his relations with southern Italy and with Constantinople Leo IX was less

fortunate. The advancing claims of the Normans, who since 1016 had been

gradually conquering the lower part of the peninsula, were opposed by the Pope,

who asserted possession for the papacy. Papal interference with the churches,

especially of Sicily, which still paid allegiance to Constantinople, aroused the

assertive patriarch of that city,

Michael Cerularius (1043-1058), who now, in

conjunction with Leo, the metropolitan of Bulgaria, closed the churches of the

Latin rite in their regions and attacked the Latin Church in a letter written by

the latter urging the old charges of Photius, and adding a condemnation of the use of

unleavened bread in the Lord’s Supper—a custom which had become common in the

West in the ninth century.

Leo IX replied by sending Cardinal Humbert and

Frederick of Lorraine, the papal chancellor, to Constantinople in 1054, by whom

an excommunication of Michael Cerularius and all his followers was laid on the

high altar of St. Sofia. This act has been usually regarded as the formal

separation of the Greek and Latin Churches. In 1053 Leo’s forces were defeated

and he himself captured by the Normans. He did not long survive this

catastrophe, dying in 1054.

On the death of Leo IX, Henry III appointed another German, Bishop Gebhard of Eichstadt, as Pope. He took the title of Victor II (1055-1057). Though friendly to the reform party, Victor II was a devoted admirer of his imperial patron, and on the unexpected death of the great Emperor in 1156, did much to secure the quiet succession of Henry III’s son Henry IV, then a boy of six, under the regency of the Empress Mother, Agnes. Less than a year later Victor II died.

This Webpage was created for a workshop held at Saint Andrew's Abbey, Valyermo, California in 1990

|

|

|

|

|

|