|

|

The Book of Kells |

|

|

The Book of Kells |

David Knowles, Christian Monasticism, ch. 2

THE tide of monastic life swept most rapidly along the northern shores of the Mediterranean to Lérins and Marseilles (400—40), the former being the home of John Cassian, and here the inspiration came directly from the east. In Gaul in general, where the Roman civilisation, half Christianised, was coming to an end in an Indian summer of leisure and literature, the monks were regarded with dislike by many of the bishops and landowners. Nevertheless, the future was theirs.

Towards the end of the fourth century Martin, bishop of Tours (d. 397), brought the life of a hermit-group first to Ligugé near Poitiers and then to the banks of the Loire at Marmoutier. Thence the monastic life spread fan-like over central and western Gaul, and from the west it passed, like the sparks of a forest fire and by a process unnoticed by chroniclers, to the Celtic regions of the British Isles.

There, in Cornwall and Wales, and still more remarkably in Ireland, monasticism of a type radically eremitical expanded rapidly from 540 to 600 and became the ruling element not only in the church but in society. In a land where cities and towns did not exist, and where the social units were the clan and tribe, monasticism when it captured the enthusiasm of a convert population rapidly became an epidemic.

When the king or chief became a Christian he often became also a monk, taking with him the whole clan. In a large monastic community, some times two or three thousand strong, the king was often abbot. Regional bishops, established by St Patrick, were supplemented or superseded by abbots with monastic spheres of influence, and the functions requiring episcopal orders were carried out by one or more of the monks, consecrated for the purpose by order of the abbot. Celtic monasticism in its golden age was austere in the extreme; physical penances (some of which still form part of pilgrimages in Ireland) such as fasting and immersion in cold water, were severe.

|

| Skellig Michael, monastic island off the Irish Coast |

|

| Beehive huts - Monastic Cells - on Skellig Michael |

Yet at the same time, in primitive conditions that would seem to render mental exertion impossible, a vivid Latin culture sprang up and a still more remarkable artistic achievement that has put Celtic monastic illuminations and metalwork among the masterpieces of art-history.

|

| Irish crucifix 8th c; Bell reliquary 11th c |

|

| Irish Gospel, St Gall 8c |

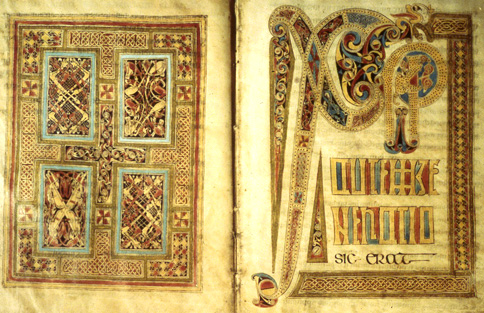

The illustrated manuscripts, such as the books of Kells and Durrow, the jewelry and the bronze bells and silver reliquaries, were made and used in wooden, wattle or drystone churches.

|

|

|

| Marov.Celt tonsure Book of Durrow | Irish Priest 7-8 c.Dublin | Muiredach Cross Tower 9-10thc |

Though the Irish monks could rival the Egyptian fathers, whose manner of life they certainly took as their model, the Celtic spirit was very different from the Coptic. We cannot imagine an eastern monk writing the following.

I have a bothy [hut] in the

wood,

none knows it save the Lord, my God;

one wall an ash, the other hazel,

and a great fern makes the door.

The doorposts are made of

heather,

and the lintel of honeysuckle;

and wild forest all around

yields mast for well-fed swine.

This size my hut; the smallest

thing;

homestead amid well-trod paths;

a woman (but blackbird clothed and seeming)

warbles sweetly from its gable.[1]

Peculiar to Celtic monachism was its predilection for exile (peregrinatio) as a form of renunciation, by which monks took to foreign lands the Christian faith and the monastic life. Iceland, the western isles of Scotland, Brittany, central Europe as far east as Regensburg and Vienna and as far south as Bobbio in Lombardy, saw the establishments of the monks of Ireland (Scotti) who took with them their culture and their rule, embodied in paintings and manuscripts that survive in the museums and libraries of Europe.

|

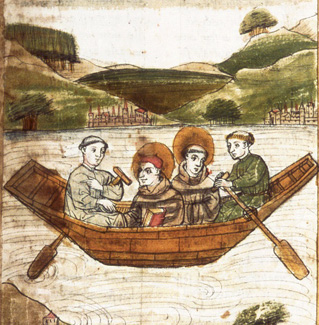

| Columbanus and Gall, 1452 St. Gall |

Foremost among these pilgrims in sanctity and influence were Columba (52l—97) the founder of Iona and the apostle of western Scotland, and Columbanus (540—615) who left his native land and after several halts arrived in the Vosges mountains, where he founded Luxeuil (c. 590).

|

| Iona, off the coast of Scotland |

|

| Iona, the abbey church |

Twenty years later, a series of adventures took him through the Rhineland and the Alps and he ended his days at Bobbio. Columbanus left a rule more austere than those of contemporary Mediterranean monachism, with severe fasts and a fierce penal code, but the heart of his monasticism was not a rule but an abbot, and throughout the family of monasteries founded or influenced by him the will of the abbot, expressed differently by different personalities, was the mainspring of the life. Meanwhile, by ways often invisible to historians, the monasteries of Lérins, of Marmoutier and of Luxeuil spread their teaching all over France and what is now known as the Low Countries.

|

|

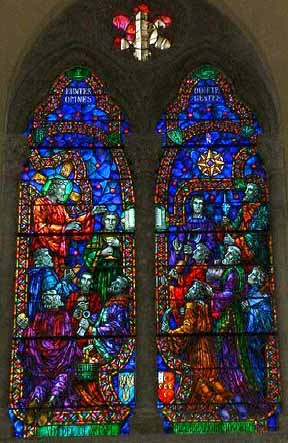

Euntes Docete

Omnes Gentes Graduates from All Hallows [Seminary in Dublin, Ireland] serving in California outnumbered all other Californian diocesan priests until the 19[?18]90s |

[1] A Celtic poem from Connaught c.670, trans. by Professor James Carney, in L. Bieler’s Ireland, Harbinger of the Middle Ages, London 1963, 59. Quoted by kind permission of Professor Bieler.

xxxx» cont xcxcxc